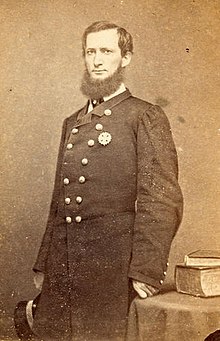

George W. L. Bickley

George W. L. Bickley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | George Washington Lafayette Bickley July 18, 1823 Russell County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | August 10, 1867 (aged 44) Baltimore, Maryland or Virginia, U.S. |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1863–1865 |

| Rank | Surgeon |

George Washington Lafayette Bickley[1][2] (July 18, 1823[3] – August 10, 1867) was the founder of the Knights of the Golden Circle, a Civil War era secret society used to promote the interests of the Southern United States by preparing the way for annexation of a "golden circle" of territories in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean which would be included into the United States as southern or slave states. Bickley was arrested by the United States government and it was during this time he wrote a letter to Abraham Lincoln expressing his distaste for Lincoln's handling of the government.

Biography[edit]

Bickley was born in Russell County, Virginia on July 18, 1823.[4] His father died of cholera in 1830 and Bickley ran away from home to live an adventurous life around the country.[5]

Medicine[edit]

By 1850, Bickley was a practicing physician in Jeffersonville (now Tazewell), Virginia. In Jeffersonville, he founded a local historical society and began writing the manuscript for the History of the Settlement and Indian War of Tazewell County, Virginia.

In 1851, Bickley moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, after being offered to serve as "Professor of Materia Medica, Therapeutics, and Medical Botany" at the Eclectic Medical Institute, an institution teaching a form of alternative medicine known as eclectic medicine.[6] Bickley had secured the offer by claiming to have been a graduate in the Class of 1842 of the University of London. Bickley stated that he had studied medicine under the renowned English physician John Elliotson, who supposedly had signed his diploma.[7] The University of London failed to find Bickley's name in their records for the list of university graduates. Furthermore, Elliotson had resigned from the university in 1838, which would falsify Bickley's claim.[8]

Writing[edit]

In 1853, Bickley published Adalaska; Or, The Strange and Mysterious Family of the Cave of Genreva, an anti-slavery novel[5] based on the premise of the Young America movement and Manifest Destiny,[9] and the Principles of Scientific Botany.[10][11] Bickley was also the publisher of the Western American Review, a New York-based conservative publication.[5]

The Knights of the Golden Circle[edit]

Hounded by creditors, Bickley left Cincinnati in the late 1850s and traveled through the East and South promoting an expedition to seize Mexico and establish a new territory for slavery.[5] He found his greatest support in Texas and managed within a short time to organize 32 chapters there.[citation needed] In the spring of 1860 the group made the first of two attempts to invade Mexico from Texas.[5] A small band reached the Rio Grande, but Bickley failed to show up with a large force he claimed he was assembling in New Orleans, and the campaign dissolved.[citation needed] In April, some KGC members in New Orleans, displeased with Bickley's inept leadership, met and expelled him,[5] but Bickley called a convention in Raleigh, North Carolina, in May and succeeded in having himself reinstated as the group's leader. Following the outbreak of the American Civil War, numerous Golden Circle members became focused on making the New Mexico territory a part of the proposed Golden Circle.[12] In May 1861, members of the KGC and Confederate Rangers attacked a building in Texas which housed a pro-Union newspaper, the Alamo Express, owned by J. P. Newcomb, and burned it down.[13]

KGC members largely aligned with Copperhead politicians who wanted a negotiated end to the war.[14] In late 1863, the Knights of the Golden Circle were reorganized (sans Bickley) as the Order of American Knights and again, early in 1864, as the Order of the Sons of Liberty, with Clement Vallandigham, the most prominent of the Copperheads, as its supreme commander, dissolved in 1864 after being exposed and members arrested and tried for treason.[15]

American Civil War[edit]

Bickley joined the Confederate States Army at the beginning of 1863 to serve as a surgeon under General Braxton Bragg.[5] However, he left for Tennessee in June 1863, and he was arrested as a Confederate spy in New Albany, Indiana, in July 1863.[5][16] He was never tried but remained under arrest until October 1865.[5]

Personal life, death and legacy[edit]

In 1850, Bickley's wife of two years died, and he left their young son in the care of another family. He moved to Cincinnati the following year, and married a widow who owned a farm in Scioto County, Ohio. They separated when he tried to sell her farm. In 1863, he had a child out of wedlock with a woman in Tennessee.[5]

Bickley died on August 10, 1867, either in Baltimore, Maryland or Virginia.[5][17] Meanwhile, the Knights of the Golden Circle became the inspiration for the Ku Klux Klan.[5][18]

References[edit]

- ^ Philip Alexander Bruce and William Glover Stanard, ed. (2000). The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Richmond, Virginia: Virginia Historical Society. p. 478.

- ^ Some sources, such as Ollinger Crenshaw's The Knights of the Golden Circle: The Career of George Bickley, published in The American Historical Review in October 1941, erroneously list Bickley's full name as "George William Leigh Bickley".

- ^ Keene, "Knights of the Golden Circle".

- ^ Keehn, David C., "Knights of the Golden Circle." For an earlier work which claims he was born in Boone County, Indian circa 1819, see Bridges, C. A. (January 1941). "The Knights of the Golden Circle: A Filibustering Fantasy". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 44 (3): 287–302. JSTOR 30235905.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kemme, Steve (August 21, 2011). "Secret Society Became Model for Ku Klux Klan". The Cincinnati Enquirer. p. 28. Retrieved November 3, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Daily Cincinnati Gazette, September 8, 1852.

- ^ Bickley's claims over his educational background were published on pp. 140–141 of the March 1853 issue (vol. 12) of the Eclectic Medical Journal.

- ^ Leslie Stephen, ed. (1889). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 17. London, England: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 264–266.

- ^ Franklin, John H. (2002). The Militant South, 1800–1861. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 125. ISBN 0252070690.

- ^ Crenshaw, p. 25.

- ^ Principles of Scientific Botany was also published in 1853 as Physiological and Scientific Botany.

- ^ Thompson, Jerry D. Colonel John Robert Baylor: Texas Indian Fighter and Confederate Soldier. Hillsboro, Tex: Hill Junior College Press, 1971. ISBN 978-0912172149.

- ^ Speck, Ernest B. "Newcomb, James Pearson | The Handbook of Texas Online|". Tshaonline.org; Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- ^ Klement, Frank L. (1955). "Copperhead Secret Societies: In Illinois during the Civil War". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 48 (2): 152–180. JSTOR 40189429.

- ^ David C. Keehn (2013). Knights of the Golden Circle: Secret Empire, Southern Secession, Civil War. Louisiana State UP. p. 173. ISBN 978-0807150047.

- ^ "Arrest of Gen. Bickley". The Abingdon Virginian. August 7, 1863. p. 4. Retrieved November 3, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "General News". Pittsburgh Gazette. August 24, 1867. p. 1. Retrieved June 2, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Pro-Slavery Group Active In 1880s". Denton Record-Chronicle. Denton, Texas. June 4, 1867. p. 4. Retrieved November 3, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

Further reading[edit]

- Crenshaw, Ollinger (October 1941). "The Knights of the Golden Circle: The Career of George Bickley". American Historical Review. 47 (1): 23–50. doi:10.2307/1838769. JSTOR 1838769.

- Curry, Richard O. (1964). A House Divided. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Dunn, Roy S. (April 1967). "The KGC in Texas, 1860–1861". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 70: 543–573.

- Frazier, Donald S.; Shaw Frazier (1995). Blood and Treasure: Confederate Empire in the Southwest. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0890966397.

- Hicks, Jimmie (July 1961). "Some Letters Concerning the Knights of the Golden Circle in Texas, 18601861". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 65: 80–86.

- Keehn, David C. (2013). Knights of the Golden Circle: Secret Empire, Southern Secession, Civil War. Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0807150047.

- May, Robert E. (1973). The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire, 1854–1861. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press.

- Milton, George F. (1942). Abraham Lincoln and the Fifth Column. New York]: Vanguard Press. OCLC 816967.

- Mingus, Scott L. (2009). Flames Beyond Gettysburg: The Gordon Expedition. Columbus, Ohio: Ironclad Publishing.

External links[edit]

- Sam Lanham Digital Library Schreiner University

- U. Texas at Austin, Knights of the Golden Circle

- Columbia Encyclopedia, Knights of the Golden Circle

- eHistory

- A 1950 radio drama, written by Richard Durham about opposition to the KGC – "Golden Circle Archived 2022-11-11 at the Wayback Machine" – presented by Destination Freedom

- 1823 births

- 1867 deaths

- People from Russell County, Virginia

- Physicians from Cincinnati

- American male novelists

- American prisoners and detainees

- 19th-century American novelists

- Confederate States Army officers

- Physicians from Virginia

- Novelists from Virginia

- Writers from Cincinnati

- Novelists from Ohio

- 19th-century American physicians

- 19th-century American male writers

- Knights of the Golden Circle

- Knights of the Golden Circle members

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States military