Today is Friday

First publication, one of 300 limited copies.[1] | |

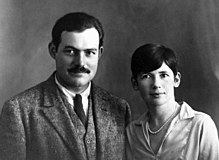

| Author | Ernest Hemingway |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Jean Cocteau[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Play/Short Stories |

| Published | 1926 |

| Publisher | The As Stable Publications/Charles Scribner's Sons |

Today is Friday is a short, one act play by Ernest Hemingway. The play was first published in pamphlet form in 1926[2] but became more widely known through its subsequent publication in Hemingway's 1927 short story collection, Men Without Women.[3] The play is a representation of the aftermath of the crucifixion of Jesus, in the form of a conversation between three Roman Soldiers and a Hebrew bartender. It is one of the few dramatic works written by Hemingway.

Background[edit]

There is little published content discussing the original publication of Today is Friday. George Monteiro simply describes the play as being published in a short story pamphlet by The As Stable Productions,[2] nevertheless, it was both written and published twice during Hemingway's years living as an expatriate in Paris.

Beginning in the early 1920s, Hemingway lived in Paris with his first wife, Hadley Richardson, working as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star. Following the publication of The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway's divorce from Richardson was finalized. Jeffrey Meyers notes that the divorce prompted Hemingway to convert to Catholicism, which may have influenced the inclusion of Today is Friday in Men Without Women.[4] He subsequently married Pauline Pfeiffer and the two holidayed in Le Grau-du-Roi in the south of France.[5] It was here that Hemingway continued planning his upcoming collection of short stories.[6] John Beall states that Hemingway was actively involved in the planning of Men Without Women while he was still writing The Sun Also Rises, and thus, it was in the South of France that he continued this work.[7] At this point, Hemingway was living comfortably, owing to both Pfeiffer's large trust fund as well as Hemingway's growing income as a writer.[5] Men Without Women was published on October 14 shortly before Hemingway and Pfeiffer moved back to the United States, making the short story collection the last work published in Hemingway's Paris years. Despite seeming so, Today is Friday is not Hemingway's first attempt at writing a piece of drama, having written a piece named No Worst Than a Bad Cold as a teenager.[8]

Plot summary[edit]

Three Roman soldiers described as "a little cock-eyed" drink red wine in a "drinking place" in the aftermath of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. They are in the company of only a Hebrew bartender named George. The first soldier orders more wine from George. The third soldier leans on a barrel in pain, complaining of a gut ache which has rendered him unable to continue drinking. George mixes a drink to fix the third soldier's gut ache. The third soldier drinks the cup and exclaims, "Jesus Christ." The three soldiers then converse about the crucifixion of Jesus they had witnessed earlier that day. The first soldier insists that "he was good in there today," while the soldiers remark on which aspects of the crucifixions they enjoy or dislike. The third soldier continues to feel unwell.

The first soldier asks the others if they "saw his girl," which is implied to be Mary Magdalene. The second soldier replies that he "knew her before he did," further implying he used her services as a prostitute before she became a follower of Jesus. The soldiers continue to talk about the crucifixion, where the first soldier admits that he stabbed Jesus with a spear while he was on the cross, insisting it was "the least I could do for him."

The three soldiers get up to leave. The second soldier tells George to add the price of the wine to his tab, refusing to pay George an advance sum reasoning that payday is on Wednesdays. Outside on the street, the second soldier refers to George with an anti-semitic term to which the third soldier continues to complain about his painful stomach.

Writing style[edit]

Hemingway's prose has been extensively analysed for its minimalistic style, which came to be known as the Iceberg theory of omission. According to Meyers, a respected biographer of Hemingway, Hemingway believed the quality of an author's work is assessable by the respective quality of the words eliminated. Furthermore, Meyers asserts that because of Hemingway's mastery of omission in this way, he then went on to become the "most influential prose stylist in the twentieth century."[4]

Robert Lamb observes that while Hemingway's prose has been 'exhaustively analysed', his specific use of dialogue has also made an equally significant impact on modern literature:[9]

During a period of three and a half years, [Hemingway] completely altered the function and technique of fictional dialogue and presented it as one of his many legacies to twentieth-century literature.[9]

Hemingway's 'deceptively simplistic'[9] dialogue is, due to the genre of the work, central to the piece. The modernity of the language and the use of American slang used by the soldiers is particularly salient given the time and setting of the play. Indeed, as Ali Zaidi comments, the soldier's dialogue is completely anachronistic.[10] While such clearly anachronistic dialogue may detract from the historical accuracy of the piece, it works to reveal the casual, irreverent attitude the soldiers have towards Jesus. Clancy Sigal commented on the style of the conversation between the soldiers as being 'casual sports-game like' and thus rendering the piece to become 'all the more vivid' to modern audiences.[11] Hemingway's ability as a playwright has been often, and understandably overlooked in the field of literary criticism. Moreover, he has rarely, if ever been referred to as a playwright, owing to his prolific career as a novelist and short story writer. Thus Today is Friday occupies a unique position in the Hemingway catalogue as a rare insight into the writer's vision of Christianity and playwriting.

Analysis[edit]

Critics have discussed the characterization of Christ, the modern Americanized language used by the soldiers and the Hebrew bartender, and a possible play within a play formula utilized by Hemingway.

Christopher Dick argues that most critics, aside from inaccurately identifying the genre of Today is Friday as a short story, also fail to notice Hemingway's "use of the dramatic as the controlling metaphor in the text."[8] Critics often interpret the repeated line, "He did good in there today," as the soldiers' apparent treatment of the crucifixion as a boxing match. An example of such a critic is Paul Smith, who insists that the conversation between the soldiers: "treats the 'main event' of Christianity as just that... a prizefight..."[12] Comparing the crucifixion to the sport of boxing, as Flora describes, reinforces the notion of the "muscular Jesus."[13] Dick, in his essay, Drama as Metaphor in Ernest Hemingway's 'Today is Friday', continues his argument that drama as a concept is the salient metaphor in the play. He quotes the lines: "That's not his play," and "I was surprised how he acted," as evidence of Hemingway's play within a play metaphor.[8]

Hemingway often referenced boxing in his writing. Today is Friday was not the only story within Men Without Women to reference boxing, the story, Fifty Grand is explicitly about a prizefight. Hemingway expressed an interest in boxing in many letters and he said, "my writing is nothing, my boxing is everything" in an interview by Josephine Herbst. He may therefore be characterizing Christ as a gallant boxer in Today is Friday, the play has been described as indicating his love for the sport in this regard.

In his book, The Hemingway Short Story: a critical appreciation, George Monteiro describes the way in which Jesus is presented in the text:

Not yet suffused with historical Christianity, mythology or legendry, Jesus emerges in the eyes of some of the Romans, not as an outlaw or a man obsessed by a vision, but as a courageous performer under extreme duress.[2]

Despite Monteiro's assertion that Jesus (in the play) has not yet assumed mythological status, Ali Zaidi argues that the casual and laconic nature of the soldiers' dialogue reveals the inference that Jesus is in fact, 'about to assume mythic proportions.' Zaidi references a tongue-in-cheek remark from the third soldier to the Hebrew bartender:

Wine-seller – You were in bad shape, Lootenant. I know what fixes up a bad stomach.

[The third Roman soldier drinks the cup down.]

3d Roman Soldier – Jesus Christ. [He makes a face.][3]

Hemingway may be alluding to Jesus' supposed ability to heal sickness.

Other critics have focused on Hemingway's potential motivation for his masculine characterization of Jesus. Lisa Tyler suggests that Today is Friday is potentially a direct response to the book The Man Nobody Knows by Bruce Barton, citing Hemingway and Barton's shared contempt for the common characterization of Jesus as 'wimpy'.[14] Instead, Jesus is characterized as macho, through the repeated allusions to boxing and his resilience. Tyler insists Hemingway's characterization of Jesus in such a way is due to his belonging to the philosophical movement, Muscular Christianity.[14]

Reception[edit]

Being one of Hemingway's lesser known works, Today is Friday has not been subject to much criticism, scholarly or otherwise. It has been treated as a "puzzling" work by Hemingway, lending mostly to the question of genre.[8] Joseph M. Flora notes that this confusion spurs from the work being included in two of Hemingway's short story collections: Men Without Women and The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories, thus treating it as a short story despite clearly being written in the form of a play.[13] The most scolding criticism of the play came from Carlos Baker in his 1969 biography, Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story, where he described the play as 'tasteless'.[15] While the play itself did not receive much, if any recognition at the time of publication, the collection it was published in, Men Without Women, did receive considerable attention. While some stories were subject to mixed reviews, Hemingway's modernist style was praised almost universally. Percy Hutchinson, in the New York Times Book Review wrote that his writing displayed "language sheered to the bone, colloquial language expended with the utmost frugality; but it is continuous and the effect is one of continuously gathering power."[16]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Vialibri Retrieved 30/9/2022.

- ^ a b c George, Monteiro (2017-03-23). The Hemingway short story: a critical appreciation. Jefferson, North Carolina. ISBN 9781476629186. OCLC 979416980.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Hemingway, Ernest (1927). Men Without Women. United States: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ a b Meyers, Jeffrey (1986). Hemingway: a biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333421260. OCLC 12977258.

- ^ a b Ernest Hemingway in context. Moddelmog, Debra., Del Gizzo, Suzanne. New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. 2013. ISBN 9781107314146. OCLC 827236389.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Mellow, James R. (1992). Hemingway: a life without consequences. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0395377772. OCLC 25508232.

- ^ Beall, John (2016). "Hemingway's and Perkins's formation of Men Without Women". The Hemingway Review. 36 (1): 94–102. doi:10.1353/hem.2016.0023. S2CID 164905151 – via GALE.

- ^ a b c d Dick, Christopher (2011-12-20). "Drama as Metaphor in Ernest Hemingway's TODAY IS FRIDAY". The Explicator. 69 (4): 198–202. doi:10.1080/00144940.2011.640923. ISSN 0014-4940. S2CID 162391218.

- ^ a b c Lamb, Robert Paul (1996). "Hemingway and the Creation of Twentieth-Century Dialogue". Twentieth Century Literature. 42 (4): 453–480. doi:10.2307/441877. JSTOR 441877.

- ^ Zaidi, Ali (2014-04-30). "The Camouflage of the Sacred in Hemingway's Short Fiction". Theory in Action. 7 (2): 104–120. doi:10.3798/tia.1937-0237.14012. ISSN 1937-0237.

- ^ Sigal, Clancy (2013). Hemingway Lives!: Why Reading Ernest Hemingway Matters Today. OR Books. doi:10.2307/j.ctt207g878. ISBN 9781939293183. JSTOR j.ctt207g878.

- ^ Smith, Paul (1989). A reader's guide to the short stories of Ernest Hemingway. Boston, Mass.: G.K. Hall. p. 150. ISBN 978-0816187942. OCLC 18961617.

- ^ a b Joseph, Flora M. (2008). Reading Hemingway's Men without women: glossary and commentary. Kent, Ohio. ISBN 9780873389433. OCLC 191927273.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Tyler, Lisa. "'He Was Pretty Good in There Today': Reviving the Macho Christ in Ernest Hemingway's 'Today Is Friday' and Mel Gibson's 'The Passion' of the Christ". Journal of Men, Masculinities and Spirituality. 1 (June 2007): 155–169 – via Informit.

- ^ Baker, Carlos (1992), Ernest Hemingway: a life story, Hurt, Christopher, 1959-, Blackstone Audio Books, ISBN 978-0786103843, OCLC 28636906

- ^ Bryer, Jackson R. (1969). Bryer, Jackson R (ed.). Fifteen Modern American Authors: A Survey of Research and Criticism. Durham, N. C.: Duke University Press.