The Vanity of Human Wishes

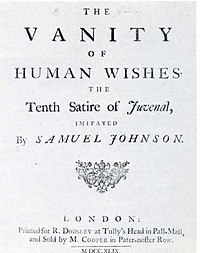

The Vanity of Human Wishes: The Tenth Satire of Juvenal Imitated is a poem by the English author Samuel Johnson.[1] It was written in late 1748 and published in 1749 (see 1749 in poetry).[2] It was begun and completed while Johnson was busy writing A Dictionary of the English Language and it was the first published work to include Johnson's name on the title page.

As the subtitle suggests, it is an imitation of Satire X by the Latin poet Juvenal. Unlike Juvenal, Johnson attempts to sympathize with his poetic subjects. Also, the poem focuses on human futility and humanity's quest after greatness like Juvenal but concludes that Christian values are important to living properly. It was Johnson's second imitation of Juvenal (the first being his 1738 poem London). Unlike London, The Vanity of Human Wishes emphasizes philosophy over politics. The poem was not a financial success, but later critics, including Walter Scott and T. S. Eliot, considered it to be Johnson's greatest poem.[3] Howard D. Weinbrot called it "one of the great poems in the English language".[4]

Background[edit]

In 1738 Johnson composed London, his first imitation of Juvenal's poetry, because imitations were popularised by those like Pope during the 18th century.[5] When Johnson replaced Edward Cave with Robert Dodsley as his publisher, he agreed with Dodsley that he would need to change the focus of his poetry.[6] Johnson's London is concerned primarily with political issues, especially those surrounding the Walpole administration, but The Vanity of Human Wishes focuses on overarching philosophical concepts.[6]

In a conversation with George Steevens, Johnson recounted that he wrote the first seventy lines "in the course of one morning, in that small house behind the church".[7] Johnson claimed that "The whole number was composed before I committed a single couplet to writing".[8] To accomplish this feat, Johnson relied on a "nearly oral form of composition" which was only possible "because of his extraordinary memory".[8] Johnson told Boswell that when he was writing poetry, he often "from laziness" only wrote down the first half of each line.[9] This remark is borne out by the manuscript of The Vanity of Human Wishes, in which the first half of each line is written in a different ink to the second half; "evidently Johnson knew that the rime words would keep the second halves in mind."[10] Although Johnson was busy after 1746 working on his Dictionary, he found time to further work on The Vanity of Human Wishes and complete his play, Irene.[11]

The first edition was published on 9 January 1749. It was the first publication by Johnson to feature his name on the title page.[12][13] It was not a financial success and only earned Johnson fifteen guineas.[13] A revised version was published in the 1755 edition of Dodsley's anthology A collection of Poems by Several Hands.[6] A third version was published posthumously in the 1787 edition of his Works, evidently working from a copy of the 1749 edition.[14] However, no independent version of the poem was published during Johnson's life beyond the initial publication.[13]

Poem[edit]

The Vanity of Human Wishes is a poem of 368 lines, written in closed heroic couplets. Johnson loosely adapts Juvenal's original satire to demonstrate "the complete inability of the world and of worldly life to offer genuine or permanent satisfaction."[16]

The opening lines announce the universal scope of the poem, as well as its central theme that "the antidote to vain human wishes is non-vain spiritual wishes":[17]

Let Observation with extensive View,

Survey Mankind from China to Peru;

Remark each anxious Toil, each eager Strife,

And watch the busy scenes of crouded Life;

Then say how Hope and Fear, Desire and Hate,

O'erspread with Snares the clouded Maze of Fate,

Where Wav'ring Man, betray'd by vent'rous Pride,

To tread the dreary Paths without a Guide;

As treach'rous Phantoms in the Mist delude,

Shuns fancied Ills, or chases airy Good.

(Lines 1–10)[18]

Later, Johnson describes the life of a scholar:

Should Beauty blunt on fops her fatal dart,

Nor claim the triumph of a letter'd heart;

Should no Disease thy torpid veins invade,

Nor Melancholy's phantoms haunt thy Shade;

Yet hope not Life from Grief or Danger free,

Nor think the doom of Man revrs'd for thee:

Deign on the passing world to turn thine eyes,

And pause awhile from Letters, to be wise;

There mark what ills the Scholar's life assail,

Toil, envy, Want, the Patron and the Jayl

(Lines 151–160)[15]

Sources[edit]

Johnson draws on personal experience as well as a variety of historical sources to illustrate "the helpless vulnerability of the individual before the social context" and the "inevitable self-deception by which human beings are led astray".[19] Both themes are explored in one of the most famous passages in the poem, Johnson's outline of the career of Charles XII of Sweden. As Howard D. Weinbrot notes, "The passage skillfully includes many of Johnson's familiar themes – repulsion with slaughter that aggrandizes one man and kills and impoverishes thousands, understanding of the human need to glorify heroes, and subtle contrast with the classical parent-poem and its inadequate moral vision."[20] Johnson depicts Charles as a "Soul of Fire", the "Unconquer'd Lord of Pleasure and of Pain", who refuses to accept that his pursuit of military conquest may end in disaster:

'Think Nothing gain'd, he cries, till nought remain,

On Moscow's Walls till Gothic Standards fly,

And all be Mine beneath the Polar Sky.'

(Lines 202–204)[21]

In a famous passage, Johnson reduces the king's military career to a cautionary example in a poem:

His Fall was destin'd to a barren Strand,

A petty Fortress, and a dubious Hand;

He left the Name, at which the World grew pale,

To point a Moral, or adorn a Tale.

(Lines 219–222)[21]

In a passage dealing with the life of a writer, Johnson drew on his own personal experience. In the original manuscript of the poem, lines 159–160 read:

There mark what ill the Scholar's life assail

Toil Envy Wantanthe Garret and the Jayl [sic][22]

The word "Garret" was retained in the first published edition of the poem. However, after the failure in 1755 of Lord Chesterfield to provide financial support for Johnson's Dictionary, Johnson included a new definition of "patron" in the Dictionary ("Patron: Commonly a wretch who supports with insolence, and is paid with flattery")[23] and revised line 160 to reflect his disillusionment:

There mark what Ills the Scholar's Life assail,

Toil, Envy, Want, the Patron, and the Jail.[24]

Imitation[edit]

Howard D. Weinbrot notes that The Vanity of Human Wishes "follows the outline of Juvenal's tenth satire, embraces some of what Johnson thought of as its 'sublimity,' but also uses it as a touchstone rather than an argument on authority." In particular, Johnson and Juvenal differ on their treatment of their topics: both of them discuss conquering generals (Charles and Hannibal respectively), but Johnson's poem invokes pity for Charles, whereas Juvenal mocks Hannibal's death.[25]

Using Juvenal as a model did cause some problems, especially when Johnson emphasised Christianity as "the only true and lasting source of hope". Juvenal's poem contains none of the faith in Christian redemption that informed Johnson's personal philosophy. In order not to violate his prototype, Johnson had to accommodate his views to the Roman model and focus on the human world, approaching religion "by a negative path" and ignoring the "positive motives of faith, such as the love of Christ".[26]

Critical response[edit]

Although Walter Scott and T. S. Eliot enjoyed Johnson's earlier poem London, they both considered The Vanity of Human Wishes to be Johnson's greatest poem.[27] Later critics followed the same trend: Howard D. Weinbrot says that "London is well worth reading, but The Vanity of Human Wishes is one of the great poems in the English language".[4] Likewise, Robert Folkenflik says "London is not Johnson's greatest poem, only because The Vanity of Human Wishes is better".[28] Robert Demaria Jr. declared the work as "Johnson's greatest poem".[6] Samuel Beckett was a devoted admirer of Johnson and at one point filled three notebooks with material for a play about him, entitled Human Wishes after Johnson's poem.[29]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Johnson 1971

- ^ The Vanity of Human Wishes; The Tenth Satire of Juvenal Imitated by Samuel Johnson. London: Printed for R. Dodsley at Tully's Head in Pall Mall. 1749. p. 1.

- ^ Eliot 1957 p. 180

- ^ a b Weinbrot 1997 p. 46

- ^ Bate 1977 p. 172

- ^ a b c d Demaria 1993 p. 130

- ^ Hill Vol. 2 pp. 313–314

- ^ a b Demaria 1993 p. 131

- ^ Boswell p. 362

- ^ Johnson 1964 p. 90f.

- ^ Lynch 2003, p. 6

- ^ Lane p. 114

- ^ a b c Yung 1984 p. 66

- ^ Johnson 1971 p. 208

- ^ a b Yung p. 65

- ^ Bate 1977 p. 279

- ^ Weinbrot 1997 p. 49

- ^ Johnson, p.83

- ^ Bate p. 281

- ^ Weinbrot p. 47

- ^ a b Johnson 1971 p. 88

- ^ Johnson 1971 p. 172

- ^ Johnson 1971 p. 211

- ^ Johnson 1971 p. 87.

- ^ Weinbrot 1997 p. 48f.

- ^ Bate 1977 p. 282

- ^ Bate 1955 p.18

- ^ Folkenflik 1997 p.107

- ^ Beckett 1986

References[edit]

- Bate, Walter Jackson (1977), Samuel Johnson, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 978-0-15-679259-2

- Bate, Walter Jackson (1955), The Achievement of Samuel Johnson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, OCLC 355413.

- Beckett, Samuel (1986), Disjecta: Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment, London: Calder Publications, ISBN 0-7145-4016-1

- Boswell, James (1980), Life of Johnson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-283531-9

- Demaria, Robert Jr. (1993), The Life of Samuel Johnson, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 1-55786-150-1.

- Eliot, T.S. (1957), On Poetry and Poets, London: Faber & Faber, ISBN 0-571-08983-6

- Folkenflik, Robert (1997), "Johnson's politics", in Clingham, Greg (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Samuel Johnson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55625-2.

- Hill, G. Birkbeck, ed. (1897), Johnsonian Miscellanies, Oxford.

- Johnson, Samuel (1964), Poems, New Haven & London: Yale University Press

- Johnson, Samuel (1971), The Complete English Poems, Harmondsworth: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-080165-0

- Lane, Margaret (1975), Samuel Johnson & his World, New York: Harpers & Row Publishers, ISBN 0-06-012496-2.

- Lynch, Jack (2003), "Introduction to this Edition", in Lynch, Jack (ed.), Samuel Johnson's Dictionary, New York: Walker & Co, pp. 1–21, ISBN 0-8027-1421-8.

- Weinbrot, Howard D. (1997), "Johnson's Poetry", in Clingham, Greg (ed.), Cambridge Companion to Samuel Johnson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55625-2

- Yung, Kai Kin; Wain, John; Robson, W. W.; Fleeman, J. D. (1984), Samuel Johnson, 1709–84, London: Herbert Press, ISBN 0-906969-45-X.

External links[edit]

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Johnson, Samuel. The Vanity of Human Wishes. 1749. Ed. Jack Lynch, Rutgers University.