Sutton Hoo helmet

| Sutton Hoo helmet | |

|---|---|

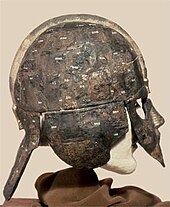

Latest reconstruction (built 1970–1971) of the Sutton Hoo helmet | |

| Material | Iron, bronze, tin, gold, silver, garnets |

| Weight | 2.5 kg (5.5 lb) estimated |

| Discovered | 1939 Sutton Hoo, Suffolk 52°05′21″N 01°20′17″E / 52.08917°N 1.33806°E |

| Discovered by | Charles Phillips |

| Present location | British Museum, London |

| Registration | 1939,1010.93 |

The Sutton Hoo helmet is a decorated Anglo-Saxon helmet found during a 1939 excavation of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial. It was buried around the years c. 620–625 CE and is widely associated with an Anglo-Saxon leader, King Rædwald of East Anglia; its elaborate decoration may have given it a secondary function akin to a crown. The helmet was both a functional piece of armour and a decorative piece of metalwork. An iconic object from an archaeological find hailed as the "British Tutankhamen",[1][2] it has become a symbol of the Early Middle Ages, "of Archaeology in general",[3] and of England.

The visage contains eyebrows, a nose, and moustache, creating the image of a man joined by a dragon's head to become a soaring dragon with outstretched wings. It was excavated as hundreds of rusted fragments; first displayed following an initial reconstruction in 1945–46, it took its present form after a second reconstruction in 1970–71.

The helmet and the other artefacts from the site were determined to be the property of Edith Pretty, owner of the land on which they were found. She donated them to the British Museum, where the helmet is on permanent display in Room 41.[4][5]

Background[edit]

The helmet was buried among other regalia and instruments of power as part of a furnished ship-burial, probably dating from the early seventh century. The ship had been hauled from the nearby river up the hill and lowered into a prepared trench. Inside this, the helmet was wrapped in cloths and placed to the left of the head of the body.[7][8] An oval mound was constructed around the ship.[9] Long afterwards, the chamber roof collapsed violently under the weight of the mound, compressing the ship's contents into a seam of earth.[10]

It is thought that the helmet was shattered either by the collapse of the burial chamber or by the force of another object falling on it. The fact that the helmet had shattered meant that it was possible to reconstruct it. Had the helmet been crushed before the iron had fully oxidised, leaving it still pliant, the helmet would have been squashed,[11][12][13] leaving it in a distorted shape similar to the Vendel[14] and Valsgärde[15] helmets.[16]

Owner[edit]

Attempts to identify the person buried in the ship-burial have persisted since virtually the moment the grave was unearthed.[17][18] The preferred candidate, with some exceptions when the burial was thought to have taken place later,[19][20] has been Rædwald;[21] his kingdom, East Anglia, is believed to have had its seat at Rendlesham, 4+1⁄4 miles (6.8 kilometres) upriver from Sutton Hoo.[22][23] The case for Rædwald, by no means conclusive, rests on the dating of the burial, the abundance of wealth and items identified as regalia, and, befitting a king who kept two altars, the presence of both Christian and pagan influences.[24][25][21]

Rædwald[edit]

What scant information is known about King Rædwald of East Anglia, according to the Anglo-Saxon historian Simon Keynes, could fit "on the back of the proverbial postage stamp".[21] Almost all that is recorded comes from the eighth-century Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum by the Benedictine monk Bede,[26] leaving knowledge of Rædwald's life, already poorly recorded, at the mercy of such things as differing interpretations of Ecclesiastical Latin syntax.[27] Bede writes that Rædwald was the son of Tytila and grandson of Wuffa, from whom the East Anglian Wuffingas dynasty derived its name.[21] In their respective works Flores Historiarum and Chronica Majora, the thirteenth-century historians Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris appear to place Tytila's death, and Rædwald's presumed concurrent succession to the throne, in 599.[note 1] Yet as reasonable as this date sounds, these historians' demonstrated difficulty with even ninth-century dates leaves ample room for doubt.[28][29]

In any event, Rædwald would have ascended to power by at least 616, around when Bede records him as raising an army on behalf of Edwin of Northumbria and defeating Æthelfrith in a battle on the east bank of the River Idle.[30] According to Bede, Rædwald had almost accepted a bribe from Æthelfrith to turn Edwin over, before Rædwald's wife persuaded him to value friendship and honour over treasure.[30][31] After the ensuing battle, during which Bede says Rædwald's son Rægenhere was slain,[31] Rædwald's power was probably significant enough to merit his inclusion in a list of seven kings said by Bede to have established rule over all of England south of the River Humber, termed an imperium;[note 2] the ninth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle expanded Bede's list to eight and applied the term bretwalda or brytenwalda,[42] literally "ruler of Britain" or "ruler of the Britains".[43][44][note 3]

Bede records Rædwald converting to Christianity while on a trip to Kent, only to be dissuaded by his wife upon his return; afterwards he kept a temple with two altars, one pagan and one Christian.[21][31][47] In the likely event that this was during Æthelberht's rule of Kent, it would have been sometime before Æthelberht's death around 618.[31][47] Rædwald's own death can be conservatively dated between 616 and 633 if using Bede,[30] whose own dates are not unquestioned.[48] Anything more specific relies on questionable post-Conquest sources.[30] Roger of Wendover claims without attribution that Rædwald died in 624.[30] The twelfth-century Liber Eliensis places the death of Rædwald's son Eorpwald, who had by then succeeded his father, in 627, meaning Rædwald would have died before then.[30] If relying solely on Bede, all that can be said is that Rædwald died sometime between his circa 616 defeat of Æthelfrith along the River Idle, and 633, when Edwin, who after Rædwald died converted Eorpwald to Christianity, died.[30]

Date[edit]

A precise date for the Sutton Hoo burial is needed for any credible attempt to identify its honoree.[49] Thirty-seven gold Merovingian coins found alongside the other objects offer the most objective means of dating the burial.[50] The coins—in addition to three blanks, and two small ingots—were found in a purse,[51] and are themselves objects of considerable interest.[52][note 4] Until 1960,[66] and largely on the basis of numismatic chronologies established during the 19th century,[67] the Sutton Hoo coins were generally dated to 650–660 AD.[68][69][70] With this range the burial was variously attributed to such monarchs as Æthelhere, Anna, Æthelwald, Sigeberht, and Ecgric, all of whom ruled and died in or around the given period.[71][72][73]

The proposed range of years, and accordingly the regal attributions, was modified by later studies that took the specific gravity of some 700 Merovingian gold coins,[74] which with some predictability were minted with decreasing purity over time, to estimate the date of a coin based on the fineness of its gold.[75] This analysis suggests that the latest coins in the purse were minted between 613 and 635 AD, and most likely closer to the beginning of this range than the end.[76][77][78] The range is a tentative terminus post quem for the burial, before which it may not have taken place; sometime later, perhaps after a period of years, the coins were collected and buried.[79] These dates are generally consistent, but not exclusive, with Rædwald.[80]

Regalia[edit]

The presence of items identified as regalia has been used to support the idea that the burial commemorates a king.[81] Some jewellery likely had significance beyond its richness.[82] The shoulder-clasps suggest a ceremonial outfit.[83][84] The weight of the great gold buckle is comparable to the price paid in recompense for the death of a nobleman; its wearer thus wore the price of a nobleman's life on his belt, a display of impunity that could be associated with few others besides a king.[82][85] The helmet displays both wealth and power, with a modification to the sinister eyebrow subtly linking the wearer to the one-eyed Germanic god Odin.[86]

Two other items, a "wand" and a whetstone, exhibit no practical purpose, but may have been perceived as instruments of power.[87] The so-called wand or rod, surviving only as a 96 mm (3.8 in) gold and garnet strip with a ring at the top, associated mountings, and traces of organic matter that may have been wood, ivory, or bone, has no discernible use but as a symbol of office.[88] On the other hand, the whetstone is theoretically functional as a sharpening stone, but exhibits no evidence of such use.[89] Its delicate ornamentation, including a carved head with a modified eye that parallels the possible allusion to Odin on the helmet,[90] suggests that it too was a ceremonial object, and it has been tentatively identified as a sceptre.[91][note 5]

Syncretism[edit]

Further evidence for the burial's association with Rædwald has been adduced from the presence of items with both Christian and pagan significance.[96] The burial is in most respects emphatically pagan; as a ship-burial, it is the manifestation of a pagan practice predating the Gregorian reintroduction of Christianity into Britain, and may have served as an implicit rejection of the encroaching Frankish Christianity.[97][98] Three groups of items, however, have clear Christian influences: two scabbard bosses, ten silver bowls, and two silver spoons.[99] The bowls and scabbard bosses each display crosses, the former with chasing and the latter with cloisonné.[100][101] The spoons are even more closely associated with the Catholic Church, inscribed as they are with a cross, and the names ΠΑΥΛΟΣ (Paulos) and ΣΑΥΛΟΣ (Saulos), both names were used by Paul the Apostle.[note 6] Even if not baptismal spoons, invoking the conversion of Paul—a theory which has been linked to Rædwald's conversion at Kent[103][104]—they are unmistakably associated with Christianity.[105][106]

Others[edit]

Rædwald may be the easiest name to attach to the Sutton Hoo ship-burial, but for all the attempts to do so, these arguments have been made with more vigour than persuasiveness.[26] The desire to link a burial with a known name, and a famous one, outstrips the evidence.[107][2] The burial is certainly a commemorative display of both wealth and power, but does not necessarily memorialise Rædwald, or a king;[108][109][110] theoretically, the ship-burial could have even been a votive offering.[111] The case for Rædwald depends heavily on the dating of the coins, yet the current dating is only precise within two decades,[80] and Merovingian coin chronologies have shifted before.[111]

The case for Rædwald depends on the assumption that modern conceptions of Middle Age wealth and power are accurate. The wealth of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial is astonishing because there are no contemporaneous parallels,[112][113] but the lack of parallels could be a quirk of survival just as much as it could be an indicator of Rædwald's wealth. Many other Anglo-Saxon barrows have been ploughed over or looted,[114] and so just as little is known about contemporary kingliness, little is known about contemporary kingly graves;[115][116][117] if there was any special significance to the items termed regalia, it could have been religious instead of kingly significance, and if anything of kingly graves is known, it is that the graves of even the mere wealthy contained riches that any king would be happy to own.[118][119][120] Distinguishing between graves of chieftains, regents, kings, and status-seeking arrivistes is difficult.[121] When Mul of Kent, the brother of King Cædwalla of Wessex, was killed in 687, the price paid in recompense was equivalent to a king's weregild.[122] If the lives of a king and his brother were equal, their graves might be equally hard to tell apart.[123][124]

Rædwald thus remains a possible but uncertain identification.[107][125] As the British Museum's former director Sir David M. Wilson wrote, while Rædwald may have been buried at Sutton Hoo, "the little word may should be brought into any identification of Rædwald. After all it may or even might be Sigeberht who died in the early 630s, or it might be his illegitimate brother if he had one (and most people did), or any other great man of East Anglia from 610 to 650."[48]

Description[edit]

Weighing an estimated 2.5 kg (5.5 lb), the Sutton Hoo helmet was made of iron and covered with decorated sheets of tinned bronze.[126][127] Fluted strips of moulding divided the exterior into panels, each of which was stamped with one of five designs.[128][129] Two depict figural scenes, another two zoophormic interlaced patterns; a fifth pattern, known only from seven small fragments and incapable of restoration, is known to occur only once on an otherwise symmetrical helmet and may have been used to replace a damaged panel.[130][131]

The existence of these five designs has been generally understood since the first reconstruction, published in 1947.[132][note 8] The succeeding three decades gave rise to an increased understanding of the designs and their parallels in contemporary imagery, allowing possible reconstructions of the full panels to be advanced, and through the second reconstruction their locations on the surface of the helmet to be redetermined.[131][139][140][141] As referred to below, the designs are numbered according to Rupert Bruce-Mitford's 1978 work.[131]

Construction[edit]

The core of the helmet was made of iron and consisted of a cap from which hung a face mask and cheek and neck guards.[126][142] The cap was beaten into shape from a single piece of metal.[143][note 9] On either side of it were hung iron cheek guards, deep enough to protect the entire side of the face, and curved inward both vertically and horizontally.[146] Two hinges per side, possibly made of leather, supported these pieces,[147] allowing them to be pulled flush with the face mask and fully enclose the face.[148]

A neck guard was attached to the back of the cap and made of two overlapping pieces: a shorter piece set inside the cap, over which attached a wide fan-like segment extending downwards, "straight from top to bottom but curved laterally to follow the line of the neck."[149] The inset portion afforded the neck guard extra movement, and like the cheek guards was attached to the cap by leather hinges.[149] Finally, the face mask was riveted to the cap on both sides and above the nose.[150] Two cutouts served as eye openings,[151] while a third opened into the hollow of the overlaid nose, thereby facilitating access to the two nostril-like holes underneath; though small, these holes would have been among the few sources of fresh air for the wearer.[152]

Atop the foundational layer of iron were placed decorative sheets of tinned bronze.[126][153] These sheets, divided into five figural or zoomorphic designs,[130][131] were manufactured by the pressblech process.[154][155][156] Preformed dies similar to the Torslunda plates[157] were covered with thin metal which, through applied force, took up the design underneath;[158][159] identical designs could thus be mass-produced from the same die, allowing for their repeated use on the helmet and other objects.[154][note 10] Fluted strips of white alloyed moulding—possibly of tin and copper, and possibly swaged[128][164]—divided the designs into framed panels, held to the helmet by bronze rivets.[128][153] The two strips running from front to back alongside the crest were gilded.[165][166] The edges of the helmet were further protected by U-shaped brass tubing, fastened by swaged bronze clips[126][167] and themselves further holding in place the pressblech panels that shared edges with the helmet.[168]

A final layer of adornments added to the helmet a crest, eyebrows, nose and mouth piece, and three dragon heads. A hollow iron crest ran across the top of the cap and terminated at front and back.[169][143] It was made of D-sectioned tubing[169][143] and consisted of two parts, an inverted U-shaped piece into the bottom of which a flat strip was placed.[144] As no traces of solder remain, the crest may have been either forged or shrunk on to the cap.[170] From either end of the crest extended an iron tang, to each of which was riveted a gilded dragon head.[171] That on the front was made of cast bronze, while the one on the rear was made of another alloy, and has now mostly degraded into tin oxide.[172]

A third dragon head, cast in bronze, faced upwards on the front of the helmet and broke the plane between face mask and cap;[173] its neck rested on the face mask, while under its eyes it was held to the cap by a large rivet shank.[174] To either side of the neck projected a hollow cast bronze eyebrow, into each of which was inlaid parallel silver wires.[175][176][177][178] Terminal boar heads were gilded, as were the undersides of the eyebrows,[179] where individual bronze cells held square garnets.[180][176][177] The eyebrows were riveted on, both to the cap at their outer ends and to the tang of a nose and mouth piece which extended upwards underneath the neck of the dragon head.[181] This tang was itself riveted to the cap,[182] one of five attachment points for the cast bronze[183] nose and mouth piece.[184]

Both sides of the nose featured "two small round projecting plates,"[185] connected by fluted and swaged strips, and concealing rivets.[186] An inlaid strip of wire extended the length of the nasal ridge, next to which the "background was punched down" and filled with niello or another metallic inlay,[187] leaving "triangles in relief" that were silvered.[183] A tracer (a "rather blunt chisel . . . used chiefly for outlining"[188]) was used to provide a grooved border on each side.[183] Running horizontally aside the nasal bridge were three punched circles per side, inlaid with silver and possibly surrounded by niello.[183]

Beneath these circles, also running horizontally from the centre of the nose to its sides were chased[183] "alternate rows of plain flutings and billeted strips which run obliquely between the central strip and a billeted lower edge."[152] This same pattern is repeated in vertical fashion on the moustache.[183][189] The curve along the bevelled lower lip, in turn, repeats the circled pattern used on the nasal bridge.[190][191] Excepting the portions covered by the eyebrows and dragon head,[151] or adorned with silver or niello,[note 11] the nose and mouth piece was heavily gilded,[183][189] which is suggested by the presence of mercury to have been done with the fire-gilding method.[187]

Breaking the symmetry of the helmet are subtle differences in the two eyebrows, and in the methods employed to fashion the cloisonné garnets. The dexter and sinister eyebrows, though at first glance identical, may have been "manufactured in different ways while being intended to look essentially the same."[195] The dexter brow is approximately 5 millimetres shorter than the sinister, and contained 43 rather than 46 inlaid silver wires and one or two fewer garnets.[196][note 12] Gilding on the dexter eyebrow was "reddish in colour" against the "yellowish" hue of the sinister,[198] while the latter contains both trace amounts of mercury and a tin corrosion product which are absent from its counterpart. Moreover, while the individual bronze cells into which the garnets are set, both on the dexter brow and on three of the four remaining dragon eyes, are underlain by small pieces of "hatched gold foil,"[180][196] those on the sinister side, and the sinister eye of the upper dragon head, have no such backing.[199] The gold backing served to reflect light back through the garnets, increasing their lustre and deepening their colour.[200] Where this backing was missing on the sinister eyebrow and one dragon eye, the luminosity of the garnets may have been dimmed by direct placement against the bronze.[201]

Dragon motifs[edit]

Three dragon heads are represented on the helmet. Two bronze-gilt dragon heads feature on either end of the iron crest running from the front to the rear of the skull cap.[144] The third sits at the junction between the two eyebrows, facing upward and given fuller form by the eyebrows, nose and moustache to create the impression of a dragon in flight.[196] The dragon soars upwards, its garnet-lined wings perhaps meant to convey a fiery contrail,[202] and in the dramatic focal point of the helmet, bares its teeth at the snake-like dragon flying down the crest.[203]

To the extent that the helmet is jewelled, such decoration is largely confined to the elements associated with the dragons.[204] Convex garnets sunk into the heads give the dragons red eyes.[175][205] The eyebrows are likewise inlaid with square garnets on their under edges, continuing outwards on each side to where they terminate in gilded boars' heads;[180][176][177][206] in addition to their secondary decorative function as wings, the eyebrows may therefore take on a tertiary form as boars' bodies.[207] The subtle differences between the eyebrows, the sinister of which lacks the gold foil backing employed on the dexter, may suggest an allusion to the one-eyed god Odin; seen in low light, with the garnets of only one eye reflecting light, the helmet may have itself seemed to have only one eye.[208][note 13]

More gold covers the eyebrows, nose and mouth piece, and dragon heads, as it does the two fluted strips that flank the crest.[173] The crest and eyebrows are further inlaid with silver wires.[211][212][213][214] Combined with the silvery colour of the tinned bronze, the effect was "an object of burnished silvery metal, set in a trelliswork of gold, surmounted by a crest of massive silver, and embellished with gilded ornaments, garnets and niello—in its way a magnificent thing and one of the outstanding masterpieces of barbaric art."[215]

Design 1: Dancing warriors[edit]

The dancing warriors scene is known from six fragments and occurs four times on the helmet.[216] It appears on the two panels immediately above the eyebrows, accounting for five of the fragments. The sixth fragment is placed in the middle row of the dexter cheek guard, on the panel closest to the face mask;[216][217] the generally symmetrical nature of the helmet implies the design's position on the opposite side as well.[134][218][219] None of the six pieces shows both warriors, although the "key fragment" depicts their crossed wrists.[220][221] A full reconstruction of the scene was inferred after the first reconstruction, when Rupert Bruce-Mitford spent six weeks in Sweden and was shown a nearly identical design on the then unpublished Valsgärde 7 helmet.[133][222][223][224][225][226][227]

Design 1 pictures two men "in civilian or ceremonial dress"[221] perhaps engaged in a spear or sword dance[228][229] "associated with the cult of Odin, the war-god."[230][231] Their outer hands each hold two spears, pointed towards their feet,[220] while their crossed hands grip swords.[133] The depiction suggests "intricate measures," "rhythm," and an "elasticity of . . . dance steps."[232] Their trailing outer legs and curved hips imply movement towards each other,[233] and they may be in the climax of the dance.[234]

The prevalence of dance scenes with a "similarity of the presentation of the scheme of movement" in contemporary Scandinavian and Northern art suggests that ritual dances "were well-known phenomena."[235] Sword dances in particular were recorded among the Germanic tribes as early as the first century AD, when Tacitus wrote of "[n]aked youths who practice the sport bound in the dance amid swords and lances," a "spectacle" which was "always performed at every gathering."[236][237][232] Whatever the meaning conveyed by the Sutton Hoo example, the "ritual dance was evidently no freak of fashion confined to a particular epoch, but was practised for centuries in a more or less unchanged form."[238]

While many contemporary designs portray ritual dances,[239] at least three examples show scenes exceptionally similar to that on the Sutton Hoo helmet and contribute to the understanding of the depicted sword dance. The same design—identical but for a different type of spears held in hand,[240] a different pattern of dress,[241] and a lack of crossed spears behind the two men[228]—is found on the Valsgärde 7 helmet, while a small fragment of stamped foil from the eastern mound at Gamla Uppsala is "so close in every respect to the corresponding warrior on the Sutton Hoo helmet as to appear at first glance to be from the same die," and may even have been "cut by the same man."[242]

The third similar design is one of the four Torslunda plates,[243] discovered in Öland, Sweden, in 1870.[244] This plate, which is complete and depicts a figure with the same attributes as on design 1, suggests the association of the men in the Sutton Hoo example with "the cult of Odin."[230][231] The Torslunda figure is missing an eye, which laser scanning revealed to have been removed by a "sharp cut, probably in the original model used for the mould."[245] Odin too lost an eye, thus evidencing the identification of the Torslunda figure as him, and the Sutton Hoo figures as devotees of him.[230][231][245]

Design 2: Rider and fallen warrior[edit]

Eight fragments and representations comprise all known instances of the second design,[246] It is thought to have originally appeared twelve times on the helmet, although this assumes that the unidentified third design, which occupies one of the twelve panels, was a replacement for a damaged panel.[247] Assuming so, the pattern occupied eight spaces on the lowest row of the skull cap (i.e., all but the two showing design 1), and two panels, one atop the other rising towards the crest, in the centre of each side.[248][249][250] All panels showing design 2 appear to have been struck from the same die.[251] The horse and rider thus move in a clockwise direction around the helmet, facing towards the rear of the helmet on the dexter side, and towards the front on the sinister side.[251]

As substantial sections of design 2 are missing, particularly from the "central area,"[252] reconstruction relies in part on continental versions of the same scene.[253] In particular, similar scenes are seen on the Valsgärde 7[254] and 8[255] helmets, the Vendel 1 helmet,[256] and on the Pliezhausen bracteate.[257] The latter piece, in particular, is both complete and nearly identical to the Sutton Hoo design.[258][259] Although a mirror image, and lacking in certain details depicted in design 2 such as the sword carried by the rider and the scabbard worn by the fallen warrior,[260][261] it suggests other details such as the small shield held by the kneeling figure.[262]

Design 2 shows a mounted warrior, spear held overhead, trampling an enemy on the ground.[263] The latter leans upwards and, grasping the reins in his left hand, uses his right hand to thrust a sword into the chest of the horse.[263] Atop the horse's rump kneels a "diminutive human, or at least anthropomorphic figure."[263] The figure is stylistically similar to the horseman. Its arms and legs are positioned identically, and, together with the rider, it clutches the spear with its right hand.[263]

The iconography underlying design 2 is unknown. It may derive from Roman models,[264][265][266] which frequently depicted images of warriors trampling vanquished enemies.[267] The subsequent development of the design, which has been found in England, Sweden, and Germany, suggests that it carried a unique meaning broadly understood in Germanic tradition.[261] Whereas the Roman examples show riders in moments of unqualified victory,[268] in Germanic representations the scene is ambiguous.[255]

The symbolism is unclear,[269][270] and elements of victory are combined with elements of defeat:[271][261] the rider directs his spear straight forward at an invisible enemy, not down at the visible enemy on the ground; though the enemy is trampled, the rider's horse is dealt a fatal wound; and a small and possibly divine figure hovers behind the rider, its body taking the form of a victorious swastika[note 15] while it seemingly guides the spear.[272] An overarching theme of the design may therefore be that of fate.[273][261] In this understanding the divine figure, possibly Odin, guides the warrior in battle, but does not completely free him from the deadly threats he faces.[273] The gods are themselves subject to the whims of fate, and can provide only limited help against the rider's enemies.[274]

Design 3: Unidentified figural scene[edit]

Seven small fragments suggest a third figural scene somewhere on the Sutton Hoo helmet. They are nevertheless too small and ambiguous to allow for the reconstruction of the scene.[138] Its presence is suggested between one and four times;[256] because other fragments demonstrate the occurrence of design 1[275] or design 2[276] on all seven available panels on the sinister side of the helmet, and on the forwardmost two panels on the dexter side (in addition to on the highest dexter panel), placement of design 3 "must have occurred towards the rear of the helmet"[256] on the dexter side.

That which remains of design 3 may suggest that a "variant rider scene" was employed to fix damage to a design 2 panel,[256] similar to how a unique pressblech design on the Valsgärde 6 helmet was likely used in repair.[277] Fragment (a) for example shows groups of parallel raised lines running in correspondence "with changes of angle or direction in the modelled surface, which on the analogy of the Sutton Hoo and other rider scenes in Vendel art, strongly suggest the body of a horse."[278] Though smaller, fragment (d) shows similar patterns and suggests a similar interpretation.[256] Fragment (b), meanwhile, shows "two concentric raised lines two millimetres apart," and "appears to be a segment of the rim of a shield which would be of the same diameter as that held by the rider in design 2."[279]

The theory of design 3 as a replacement panel gains some support from damage towards the back of the helmet, but is contradicted by the placement of fragment (c). The crest, complete for 25.5 cm (10.0 in) from front to back, is missing 2 cm (0.79 in) above the rear dragon head.[280] This head is itself mostly missing, and is absent from the 1945–46 reconstruction.[281][282][283] These missing portions are offered by Bruce-Mitford as a possible indication that the helmet at one time suffered damage necessitating the restoration of at least one design 2 panel with a new equestrian scene.[284]

This theory does not explain why the rear crest and dragon head would not have been themselves repaired, however, and it is not helped by fragment (c). This fragment is an edge piece placed in the 1970–71 reconstruction on the dexter rear of the helmet at the bottom left of a panel where either design 2 or design 3 is expected, yet is "an isolated element quite out of context with any other surviving fragment and with what appears to be the subject matter of the design 3 panel."[279] Bruce-Mitford suggests that as it is an edge piece it may have originally been a scrap placed under another piece to fill a gap, for it is "otherwise inexplicable."[279][note 16]

Design 4: Larger interlace[edit]

Occurring on the cheek guards, the neck guard and the skull cap,[250] the larger interlace pattern was capable of a complete reconstruction.[286] Unlike the two identified figural scenes, partial die impressions of design 4 were used in addition to full die impressions.[286] Blank spaces on the skull cap and neck guard, devoid of decorative designs, allowed for impressions of design 4 that are nearly or entirely complete.[287] On the cheek guards, by contrast, which are irregularly shaped and fully decorated, the interlace designs appear in partial, and sometimes sideways, fashion.[288]

Design 4 depicts a single animal, or quadruped, in ribbon style, and has a billeted border on all sides.[289] The head of the animal is located in the upper centre of the panel.[290] The eye is defined by two circles; the rest of the head, comprising two separate but intertwined ribbons, surrounds it.[290] A third ribbon, representing the jaws and mouth, is beneath the head.[290] On the left it begins as a small billeted ribbon that descends into a pellet-filled twist, passes under itself, and emerges as a larger billeted ribbon.[290]

Circling counterclockwise, it passes over and then under a separate ribbon that represents the body, under it again, then over and under one of the ribbons representing the head.[290] It emerges as a second pellet-filled twist, again forms a billeted ribbon, and terminates in a shape resembling a foot.[289] A fourth ribbon, forming the animal's neck, starts from the head and travels downwards, under and over a ribbon forming a limb, and terminating in a pellet-filled twist, at the bottom right corner, representing the front hip.[290] Two limbs leave from the hip.[290] One immediately terminates in the border; the second travels upwards as a billeted ribbon, under and over the neck, and ends in another hip ("illogically", per Bruce-Mitford).[290]

Another short limb, filled with pellets, emerges from this hip and terminates in a foot.[290] The animal's body, meanwhile, is formed by another billeted ribbon that connects the front hip in the lower right, with the rear hip, in the top left.[290] From right to left it travels under, under, and over the jaws and mouth, under a billeted ribbon representing legs, and then connects to the rear hip.[290] The rear hip, like the front hip, is connected to two limbs.[290] One is a small, pellet-filled twist.[290] The other travels downwards as a billeted ribbon to the bottom left corner, where it terminates in another hip that connects to a pellet-filled limb, and then a foot.[290]

The design is representative of what Bernhard Salin termed "Design II" Germanic animal ornament.[291]

Design 5: Smaller interlace[edit]

The smaller interlace pattern covered the face mask, was used prominently on the neck guard, and filled in several empty spaces on the cheek guards.[286] It is a zoomorphic design, like the larger interlace, and shows "two animals, upside down and reversed in relation to each other, whose backward-turning heads lie towards the centre of the panel."[291]

Function[edit]

The Sutton Hoo helmet was both a functional piece of battle equipment and a symbol of its owner's power and prestige. It would have offered considerable protection if ever used in battle,[292] and as the richest known Anglo-Saxon helmet, indicated its owner's status.[293] As it is older than the man with whom it was buried, the helmet may have been an heirloom,[294][284] symbolic of the ceremonies of its owner's life and death;[295][296][297] it may further be a progenitor of crowns, known in Europe since around the twelfth century,[298][299] indicating both a leader's right to rule and his connection with the gods.[86]

Whether or not the helmet was ever worn in battle is unknown, but though delicately ornamented, it would have done the job well.[292] Other than leaving spaces to allow movement of the shoulders and arms, the helmet leaves its wearer's head entirely protected,[281] and unlike any other known helmet of its general type, it has a face mask, one-piece cap, and solid neck guard.[300] The iron and silver crest would have helped deflect the force of falling blows,[301][302][303] and holes underneath the nose would have created a breathable—if stifling[304]—environment within.[305] If two suppositions are to be taken as true—that damage to the back of the helmet occurred before the burial,[306] and that Raedwald is properly identified as the helmet's owner—then the helmet can be at least described as one that saw some degree of use during its lifetime, and one that was owned by a person who saw battle.[307]

Beyond its functional purpose, the Sutton Hoo helmet would have served to convey the high status of its owner. Little more than an iron cap, such as the helmets from Shorwell and Wollaston,[308][309][310] would be needed if one only sought to protect one's head.[311][312] Yet helmets were objects of prestige in Anglo-Saxon England, as indicated by archaeological, literary, and historical evidence.[313] Helmets are relatively common in Beowulf, an Anglo-Saxon poem focused on royals and their aristocratic milieu,[314][315][316] but rarely found today; only six are currently known, despite the excavation of thousands of graves from the period.[317][318][319]

Much as this could reflect poor rates of artefact survival, or even recognition—the Shorwell helmet was at first misidentified as a "fragmentary iron vessel",[320] the Wollaston helmet as a bucket,[321] and a plain Roman helmet from Burgh Castle as "cauldron fragments"[322]—the extreme scarcity suggests that helmets were never deposited in great numbers, and signified the importance of those wearing them.[319]

That the Sutton Hoo helmet was likely around 100 years old when buried suggests that it may have been an heirloom, a sample from the royal treasury passed down from another generation.[294][284][323] The same suggestion has been made for the shield from the burial, as both it and the helmet are objects with distinct Swedish influence.[324][325][326][327] The importance of heirloom items is well documented in poetry;[328] every sword of note in Beowulf, from Hrunting to Nægling, has such a history,[329] and the poem's hero, whose own pyre is stacked with helmets,[330] uses his dying words to bestow upon his follower Wiglaf a gold collar, byrnie, and gilded helmet.[331][332] The passing of the helmet, from warrior to warrior and then to the ground, would have been symbolic of the larger ceremony of the passing of titles and power,[295][296] and the final elegy for the man buried in the mound.[297]

The helmet easily outstrips all other known examples in terms of richness.[333][334][293] It is uniquely from a presumed royal burial,[333] at a time when the monarchy was defined by the helmet and the sword.[335][336] Helmets, perhaps because they were worn by rulers so frequently, may have come to be identified as crowns.[319][337] Though many intermediate stages in the typological and functional evolution are yet unknown,[338] the earliest European crowns that survive, such as the turn-of-the-millennium crown of Saint Stephen and of Constance of Aragon, share the same basic construction of many helmets, including the Coppergate example, contemporaneous with the one from Sutton Hoo: a brow band, a nose-to-nape band, and lateral bands.[299] A divine right to rule, or at least a connection between gods and leader—also seen on earlier Roman helmets, which sometimes represented Roman gods[339]—may have been implied by the alteration to the sinister eyebrow on the Sutton Hoo helmet; the one-eyed appearance could only have been visible in low light, such as when its wearer was in a hall, the seat of the king's power.[86]

Context and parallels[edit]

Unique in many respects, the Sutton Hoo helmet is nevertheless inextricably linked to its Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian contexts. It is one of only six known Anglo-Saxon helmets, along with those found at Benty Grange (1848), Coppergate (1982), Wollaston (1997), Shorwell (2004) and Staffordshire (2009),[318] yet is closer in character to finds in Sweden at Vendel (1881–1883) and Valsgärde (1920s).[340] At the same time, the helmet shares "consistent and intimate" parallels with those characterised in the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf,[341] and, like the Sutton Hoo ship-burial as a whole,[342] has had a profound impact on modern understandings of the poem.[343]

Helmets[edit]

Within the corpus of sixth- and seventh-century helmets, the Sutton Hoo helmet is broadly classified as a "crested helmet," distinct from the continental spangenhelm and lamellenhelm.[344][345] 50 helmets are so classified,[note 17] although barely more than a dozen can be reconstructed and a few are so degraded that they are not indisputably from helmets.[351][352] Excepting an outlier fragment found in Kiev, all crested helmets originate from England or Scandinavia.[353][354]

Of the crested helmets the Sutton Hoo helmet belongs to the Vendel and Valsgärde class, which themselves derive from the Roman infantry and cavalry helmets of the fourth and fifth century Constantinian workshops.[355] Helmets were found in graves 1, 12 and 14 at Vendel (in addition to partial helmets in graves 10 and 11), and in graves 5, 6, 7 and 8 at Valsgärde.[242] The Sutton Hoo example shares similarities in design, yet "is richer and of higher quality" than its Scandinavian analogues; its differences may reflect its manufacture for someone of higher social status, or its closer temporal proximity to the antecedent Roman helmets.[356]

| Helmet | Location | Completeness | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sutton Hoo | England: Sutton Hoo, Suffolk | Helmet | ||

| Coppergate | England: York | Helmet | ||

| Benty Grange | England: Derbyshire | Helmet | ||

| Wollaston | England: Wollaston, Northamptonshire | Helmet | [357][358][359][360][361][362][363][364][365][366] | |

| Staffordshire | England: Staffordshire | Helmet | [367][368][369] | |

| Guilden Morden | England: Guilden Morden, Cambridgeshire | Fragment (boar) | [370][371][372][373][374][375][376] | |

| Caenby | England: Caenby, Lincolnshire | ? | Fragment (foil) | [377][378][379][380][381][382][383][384][374][385] |

| Rempstone | England: Rempstone, Nottinghamshire | Fragment (crest) | [386][374][375] | |

| Asthall | England: Asthall, Oxfordshire | ? | Fragments (foil) | [387][388][389][382][390][384][391][392] |

| Icklingham | England: Icklingham, Suffolk | Fragment (crest) | [393][394][374][375] | |

| Horncastle | England: Horncastle, Lincolnshire | Fragment (crest) | [395][396] | |

| Tjele | Denmark: Tjele, Jutland | Fragment (eyebrows/nose) | [397][398][399][400][401][383][402][403] | |

| Gevninge | Denmark: Gevninge, Lejre, Sjælland | Fragment (eye) | [404][405][406][407] | |

| Gjermundbu | Norway: Norderhov, Buskerud | Helmet | [408][409][410][411][412][413][414] | |

| Øvre Stabu | Norway: Øvre Stabu, Toten, Oppland | ? | Fragment (crest) | [415][409][416][347][417][394] |

| By | Norway: By, Løten, Hedmarken | Fragment | [418][416][394][417] | |

| Vestre Englaug | Norway: Vestre Englaug, Løten, Hedmarken | Fragment | [419][420][421][422][418][416][423][394] | |

| Nes | Norway: Nes, Kvelde, Vestfold | Fragment | [424][421][416][423][394] | |

| Lackalänga | Sweden | Fragment | ||

| Sweden | Sweden: Unknown location (possibly central) | Fragment (crest) | [425][426][427][428] | |

| Solberga | Sweden: Askeby, Östergötland | |||

| Gunnerstad | Sweden: Gamleby, Småland | Fragments | ||

| Prästgården | Sweden: Prästgården, Timrå, Medelpad | Fragments (crest) | [338][426][384][429] | |

| Vendel I | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Vendel X | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Fragments (crest/camail) | [430][431][432][427][433][347][384] | |

| Vendel XI | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Fragments | [434][435][421][436][427][437][347][428] | |

| Vendel XII | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Vendel XIV | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Valsgärde 5 | Sweden: Valsgärde, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Valsgärde 6 | Sweden: Valsgärde, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Valsgärde 7 | Sweden: Valsgärde, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Valsgärde 8 | Sweden: Valsgärde, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Gamla Uppsala | Sweden: Gamla Uppsala, Uppland | Fragments (foil) | [438][439][440][441][442][443][384][444] | |

| Ultuna | Sweden: Ultuna, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Vaksala | Sweden: Vaksala, Uppland | Fragments | [445][446] | |

| Vallentuna | Sweden: Vallentuna, Uppland | Fragments | [447][426][384] | |

| Landshammar | Sweden: Landshammar, Spelvik, Södermanland | Fragments | ||

| Lokrume | Sweden: Lokrume, Gotland | Fragment | [448][449][450][451][452][426][453][454][455][456][457] | |

| Broe | Sweden: Högbro Broe, Halla, Gotland | Fragments | [458][459][460][461][462][463][451][426][464] | |

| Gotland (3) | Sweden: Endrebacke, Endre, Gotland | Fragment | ||

| Gotland (4) | Sweden: Barshaldershed, Grötlingbo, Gotland | Fragment (crest?) | [465][461][466][427][242][443][467] | |

| Hellvi | Sweden: Hellvi, Gotland | Fragments (eyebrow) | [468][469][470][471][472][413][467][473] | |

| Gotland (6) | Sweden: Unknown, Gotland | Fragment | ||

| Gotland (7) | Sweden: Hallbjens, Lau, Gotland | Fragments | [474][469][475][427][242][443][467] | |

| Gotland (8) | Sweden: Unknown, Gotland | ? | Fragment (crest) | [476][469][477][242][443][467] |

| Gotland (9) | Sweden: Grötlingbo(?), Gotland | ? | Fragment (crest) | [478][469][479][242][443][467] |

| Gotland (10) | Sweden: Gudings, Vallstena, Gotland | ? | Fragment (crest) | [480][469][481][242][443][467] |

| Gotland (11) | Sweden: Kvie and Allekiva, Endre, Gotland | ? | Fragment (crest) | [482][469][483][242][443][467] |

| Uppåkra | Sweden: Uppåkra, Scania | Fragment (eyebrow/boars) | [484][485][486][487][405][488][489] | |

| Desjatinna | Ukraine: Kiev | Fragment (eyebrows/nose) | [490][491] |

Anglo-Saxon[edit]

Although the Staffordshire helmet, currently undergoing research and reconstruction, may prove to be more closely related, the four other known Anglo-Saxon helmets share only minor details in decoration and few similarities in construction with the example from Sutton Hoo. In construction its cheek guards and crest link it to its Anglo-Saxon contemporaries, yet it remains the only helmet to have a face mask, fixed neck guard, or cap raised from a single piece of metal. Decoratively it is linked by its elaborate eyebrows, boar motifs, and wire inlays, but is unparalleled in its extensive ornamentation and pressblech patterns. The similarities likely reflect "a set of traditional decorative motifs which are more or less stable over a long period of time";[492] the differences may simply highlight the disparity between royal and patrician helmets, or may indicate that the Sutton Hoo helmet was more a product of its Roman progenitors than its Anglo-Saxon counterparts.[493]

The primary structural similarity between the Sutton Hoo and other Anglo-Saxon helmets lies in the presence of cheek guards, a feature shared by the Coppergate, Wollaston and Staffordshire helmets,[494][495][321][496] yet generally missing from their Scandinavian counterparts.[300] The construction of the Sutton Hoo helmet is otherwise largely distinguished from all other Anglo-Saxon examples. Its cap is unique in having been raised from a single piece of iron.[497] The caps of the other helmets were each composed of at least eight pieces. On the iron Coppergate, Shorwell and Wollaston helmets, a brow band was joined by a nose-to-nape band, two lateral bands, and four infill plates,[498][499][500][501][321] while the Benty Grange helmet was constructed from both iron and horn.[502][503]

A brow band was joined both by nose-to-nape and ear-to-ear bands and by four strips subdividing the resultant quadrants into eighths.[504] Eight pieces of horn infilled the eight open spaces, with the eight joins each covered by an additional strip of horn.[502] The Sutton Hoo helmet is the only known Anglo-Saxon helmet to have either a face mask or a fixed neck guard;[300] the Coppergate and Benty Grange helmets, the only others to have any surviving form of neck protection,[note 19] used camail and horn, respectively,[508][509][510] and together with the Wollaston helmet protected the face by use of nose-to-nape bands elongated to form nasals.[511][512][513][310]

The decorative similarities between the Sutton Hoo helmet and its Anglo-Saxon contemporaries are peripheral, if not substantial. The helmets from Wollaston and Shorwell were designed for use rather than display;[373][308] the latter was almost entirely utilitarian, while the former, "a sparsely decorated 'fighting helmet,'"[310] contained only a boar crest and sets of incised lines along its bands as decoration.[514][515] Its boar crest finds parallel with that atop the Benty Grange helmet,[516] the eyes on which are made of garnets "set in gold sockets edged with filigree wire . . . and having hollow gold shanks . . . which were sunk into a hole" in the head.[517]

Though superficially similar to the garnets and wire inlays on the Sutton Hoo helmet, the techniques employed to combine garnet, gold and filigree work are of a higher complexity more indicative of Germanic work.[517] A helmet sharing more distinct similarities with the Sutton Hoo example is the one from Coppergate. It features a crest and eyebrows, both hatched[518][519] in a manner that may reflect "reminiscences or imitations of actual wire inlays"[520][521] akin to those on the Sutton Hoo helmet.[522] The eyebrows and crests on both helmets further terminate in animal heads, though in a less intricate manner on the Coppergate helmet,[523] where they take a more two-dimensional form. These similarities are likely indicative of "a set of traditional decorative motifs which are more or less stable over a long period of time," rather than of a significant relationship between the two helmets.[492]

Compared with the "almost austere brass against iron of the Coppergate helmet," the Sutton Hoo helmet, covered in tinned pressblech designs and further adorned with garnets, gilding, and inlaid silver wires, radiates "a rich polychromatic effect."[492] Its appearance is substantially more similar to the Staffordshire helmet, which, while still undergoing conservation, has "a pair of cheek pieces cast with intricate gilded interlaced designs along with a possible gold crest and associated terminals."[524] Like the Sutton Hoo helmet it was covered in pressblech foils,[525] including a horseman and warrior motif so similar to design 3 as to have been initially taken for the same design.[369]

[edit]

This section may contain an excessive number of citations. (February 2021) |

-

Vendel 1

-

Vendel 12

-

Vendel 14

-

Valsgärde 5

-

Valsgärde 6

-

Valsgärde 8

-

Ultuna

Significant differences in the construction of the Sutton Hoo and Scandinavian helmets belie significant similarities in their designs. The Scandinavian helmets that are capable of restoration were constructed more simply than the Sutton Hoo helmet. None has a face mask,[300] solid neck guard,[526] or cap made from one piece of metal,[300] and only two have distinct cheek guards.[300][527] The neck guards "seem without exception to have [been] either iron strips or protective mail curtains."[528] The helmets from Ultuna, Vendel 14 and Valsgärde 5 all used iron strips as neck protection; five strips hung from the rear of the Vendel 14[529][530] and Valsgärde 5[531] brow bands,[532][533] and though only two strips survive from the Ultuna helmet,[534][535] others would have hung alongside them.[536]

Camail was used on the remaining helmets, from Valsgärde 6,[537][538][528][539] 7[540][541][539] and 8,[528][539] and from Vendel 1[542][543][537][539] and 12.[544][545][540][528][539] Fragmentary remains from Vendel 10[540][528] and 11,[546] and from Solberga,[427][539] likewise suggest camail. In terms of cheek protection, only two helmets had something other than continuations of the camail or iron strips used to protect the neck.[300][527] The Vendel 14 helmet had cheek guards, but of "a differing version well forward on the face" of those on the Sutton Hoo helmet.[300] Though not fully reconstructable,[547] fragments from the Broe helmet suggest a configuration similar to those on the Vendel 14 helmet.[548] Finally, the widely varying caps on each Scandinavian helmet all share one feature: None is similar to the cap on the Sutton Hoo helmet.[300]

The basic form of the helmets from Vendel, Valsgärde, Ultuna and Broe all started with a brow band and nose-to-nape band. The Ultuna helmet had its sides filled in with latticed iron strips,[549][550] while each side on the Valsgärde 8 helmet was filled in with six parallel strips running from the brow band to the nose-to-nape brand.[551][552] The remaining four helmets—excepting those from Vendel 1 and 10,[553] and Broe,[554] which are too fragmentary to determine their exact construction—all employed two lateral bands and sectional infills.

The Vendel 14 helmet had eight infill plates, one rectangular and one triangular per quadrant;[555][556][557] that from Valsgärde 7 helmet used four infill plates, one for each quadrant;[558][552] the one from Valsgärde 6 also used identical infills for each quadrant, but with "elaborate"[559] Y-shaped iron strips creating a latticed effect;[560][552] and the Valsgärde 5 example filled in the back two quadrants with latticed iron strips, and the front two quadrants each with a rectangular section of lattice work and a triangular plate.[561][562]

The decorative and iconographic similarities between the Sutton Hoo and Scandinavian helmets are remarkable; they are so pronounced as to have helped in the reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet's own imagery, and to have fostered the idea that the helmet was made in Sweden, not Anglo-Saxon England. Its ornate crest and eyebrows are parallelled by the Scandinavian designs, some of which replicate or imitate its silver wire inlays; garnets adorn the helmets from Sutton Hoo and Valsgärde 7; and the pressblech designs covering the Sutton Hoo and Scandinavian helmets are both ubiquitous and iconographically intertwined. Although the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian helmets almost universally have crests, hence their general classification as "crested helmets,"[563][348] the wire inlays in the Sutton Hoo crest find their closest parallel in the "Vendel-type helmet-crests in which such wire-inlay patterns are imitated in casting or engraving."[520][521]

Thus the crests from the Vendel 1[564][542][565][543][566][520][302] and 12[544][565][567] helmets both have chevrons mimicking the Sutton Hoo inlays, as does the Ultuna helmet[565] and all those from Valsgärde—as well as fragments from Vendel 11[568][565][569][570] and from central Sweden.[570] The eyebrows of Scandinavian helmets are yet more closely linked, for those on the Broe helmet[460][461][462] are inlaid with silver wires,[472][473] while the Lokrume helmet fragment is either inlaid or overlaid with silver.[448][571][572][472]

Even those eyebrows without silver tend to be ornate. The Valsgärde 8,[573] Vendel 1[542][543] and Vendel 10[544][567] eyebrows have chevrons following the same pattern as their crests, and though it lacks such an elaborate crest,[574][575] the Vendel 14 helmet likewise has sets of parallel lines engraved longitudinally into the eyebrows;[576][556] the lone eyebrow found at Hellvi is similarly decorated.[468][469][470][472][473] Those that lack chevrons—singular finds from Uppåkra[484][485][486][487][488][489] and Gevninge[404][577][407] in addition to the helmets from Valsgärde 5, 6,[578] and 7[579]—are still highly decorated, with the garnet-encrusted Valsgärde 7 eyebrows being the only known parallel to those from Sutton Hoo.[579]

In all these decorative respects, two Scandinavian helmets, from Valsgärde 7 and Gamla Uppsala, are uniquely similar to the Sutton Hoo example.[580] The Valsgärde 7 crest has a "cast chevron ornament";[541] the helmet "is 'jeweled', like the Sutton Hoo helmet, but showing a greater use of garnets";[581] and it contains figural and interlace pressblech patterns, including versions of the two figural designs used on the Sutton Hoo helmet.[581] Unlike on the Sutton Hoo helmet, the Valsgärde 7 rider and fallen warrior design was made with two dies, so that those on both dexter and sinister sides are seen moving towards the front, and they contain some "differing and additional elements."[581]

The Valsgärde 7 version of the dancing warriors design, however, contains "only [one] major iconographic difference," the absence of two crossed spears behind the two men.[228] The scenes are so similar that it was only with the Valsgärde 7 design in hand that the Sutton Hoo design could be reconstructed.[133][224][225][227] The Gamla Uppsala version of this scene is even more similar. It was at first thought to have been struck from the same die,[582][242] and required precise measurement of the original fragments to prove otherwise.[583] Though the angles of the forearms and between the spears are slightly different, the Gamla Uppsala fragment nonetheless provides "the closest possible parallel" to the Sutton Hoo design.[220]

Taken as a whole, the Valsgärde 7 helmet serves "better than any of the other helmets of its type to make explicit the East Scandinavian context of the Sutton Hoo helmet."[541] Its differences, perhaps, are explained by the fact that it was in the grave of a "yeoman-farmer," not royalty.[222] "Royal graves strictly contemporary with [it] have not yet been excavated in Sweden, but no doubt the helmets and shields such graves contained would be nearer in quality to the examples from Sutton Hoo."[222] It is for this reason that the Gamla Uppsala fragment is particularly interesting;[300][584] coming from a Swedish royal cremation and with "the dies seemingly cut by the same hand,"[300] the helmet may originally have been similar to the Sutton Hoo helmet.[220]

Roman[edit]

-

Berkasovo 1

-

Deurne

-

Augsburg-Pfersee

Whatever its Anglo-Saxon or Scandinavian origins, the Sutton Hoo helmet is descended from the Roman helmets of the fourth and fifth century termed 'ridge helmets'.[585] Its construction—featuring a distinctive crest, solid cap and neck and cheek guards, face mask, and leather lining—bears clear similarities to these earlier helmets.[586] Numerous examples have a crest similar to that on the Sutton Hoo helmet, such as those from Deurne, Concești, Augsburg-Pfersee, and Augst, and the Berkasovo 1 and 2 and Intercisa 2 and 4 helmets.[587] Meanwhile, the one-piece cap underneath, unique in this respect among the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian helmets,[497] represents the end of a Greek and Roman technique.[588]

Primarily used in first and second century helmets of the early Roman Empire[589][590] before being replaced by helmets with a bipartite construction[591]—hence the role of the crest in holding the two halves together[592]—the practice is thought to have finally been forgotten around 500 AD.[588][593] The solid iron cheek guards of the Sutton Hoo helmet, likewise, derive from the Constantinian style, and is marked by cutouts towards the back.[585] The current reconstruction partly assumes the Roman influence of the cheek guards; Roman practice reinforced the belief that leather hinges were employed,[594] while the sinister and dexter cheek guards were swapped after an expert on arms and armour suggested that the cutouts should be at the back.[595] The neck guard similarly assumes leather hinges,[596][note 20] and with its solid iron construction—like the one-piece cap, unique among Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian helmets[598]—is even more closely aligned with the Roman examples,[599] if longer than was typical.[600]

The Witcham Gravel helmet from the first century AD[601][602] has such a broad and deep neck guard,[603] and solid projecting guards are found on the Deurne and Berkasovo 2 helmets.[604] Another feature of the Sutton Hoo helmet unparalleled by its contemporaries—its face mask[300]—is matched by Roman examples.[605] Among others the Ribchester helmet from the turn of the first century AD,[606] and the Emesa helmet from the early first century AD,[607][608][note 21] each include an anthropomorphic face mask; the latter is more similar to the Sutton Hoo helmet,[605] being affixed to the cap by a single hinge rather than entirely surrounding the face.[611][612][605] Finally, the suggestion of a leather lining in the Sutton Hoo helmet, largely unsupported by positive evidence[613] other than the odd texture of the interior of the helmet,[614][615][592] gained further traction by the prevalence of similar linings in late Roman helmets.[616][617][note 22]

Several of the decorative aspects of the Sutton Hoo helmet, particularly its white appearance, inlaid garnets, and prominent rivets, also derive from Roman practice.[586] Its tinned surface compares with the Berkasovo 1 and 2 helmets and those from Concești, Augsburg-Pfersee, and Deurne.[586][621] The Berkasovo 1 and Budapest helmets are further adorned with precious or semi-precious stones, a possible origin for the garnets on the Sutton Hoo and Valsgärde 7 helmets.[622] Finally, the prominent rivets seen on some of the crested helmets, such as those from Valsgärde 8 and Sutton Hoo, may have been inspired by the similar decorative effect achieved by the rivets on Roman helmets like the Berkasovo 2 and Duerne examples.[623]

Beowulf[edit]

Understandings of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial and Beowulf have been intertwined ever since the 1939 discovery of the former. "By the late 1950s, Beowulf and Sutton Hoo were so inseparable that, in study after study, the appearance of one inevitably and automatically evoked the other. If Beowulf came on stage first, Sutton Hoo was swiftly brought in to illustrate how closely seventh-century reality resembled what the poet depicted; if Sutton Hoo performed first, Beowulf followed close behind to give voice to the former's dumb evidence."[624] Although "each monument sheds light on the other,"[625] the connection between the two "has almost certainly been made too specific."[626]

Yet "[h]elmets are described in greater detail than any other item of war-equipment in the poem,"[627] and some specific connections can be drawn. The boar imagery, crest and visor all find parallels in Beowulf, as does the helmet's gleaming white and jewelled appearance. Though the Sutton Hoo helmet cannot be said to fully mirror any one helmet in Beowulf, the many isolated similarities help ensure that "despite the limited archaeological evidence no feature of the poetic descriptions is inexplicable and without archaeological parallel."[628]

Helmets with boar motifs are mentioned five times in Beowulf,[629][630][631][632] and fall into two categories: those with freestanding boars and those without.[633][634][635] As Beowulf and his fourteen men disembark their ship and are led to see King Hrothgar, they leave the boat anchored in the water:

Gewiton him þa feran, flota stille bad, |

So they went on their way. The ship rode the water, |

Such boar-shapes may have been like those on the Sutton Hoo helmet, terminating at the ends of the eyebrows and looking out over the cheek guards.[633][176][177] Beowulf himself dons a helmet "set around with boar images"[638] (besette swin-licum[639]) before his fight with Grendel's mother; further described as "the white helmet . . . enhanced by treasure" (ac se hwita helm . . . since geweorðad[640]), a similar description could have been applied to the tinned Sutton Hoo example.[176][641][642][619][643] (The two helmets would not have been identical, however; Beowulf's was further described as "encircled in lordly links"[644]—befongen frea-wrasnum[645]—a possible reference to the type of chain mail on the Valsgärde 6 and 8 helmets that provided neck and face protection.[646][647])

The other style of boar adornment, mentioned three times in the poem,[648] appears to refer to helmets with a freestanding boar atop the crest.[649][634][635] When Hrothgar laments the death of his close friend Æschere, he recalls how Æschere was "my right hand man when the ranks clashed and our boar-crests had to take a battering in the line of action."[650][651] These crests were probably more similar to those on the Benty Grange and Wollaston helmets,[649][634][635] a detached boar found in Guilden Morden,[370][371][372] and those seen in contemporary imagery on the Vendel 1 and Valsgärde 7 helmets and on the Torslunda plates.[652][653]

Alongside the boar imagery on the eyebrows, the silver inlays of the crest on the Sutton Hoo helmet find linguistic support in Beowulf. The helmet presented to Beowulf as a "victory gift" following his defeat of Grendel is described with identical features:

no he þære feohgyfte |

It was hardly a shame to be showered with such gifts |

This portion of the poem was thought "probably corrupt" until the helmet was discovered, with the suggestion that "the scribe himself does not appear to have understood it";[656] the meaning of "the notorious wala,"[343] in particular, was only guessed at.[301][657][note 23] The term is generally used in Old English to refer to a ridge of land, not the crest of a helmet;[667] metaphorically termed wala in the poem, the crest is furthermore wirum bewunden, literally "wire bewound" (bound with wires).[668][669][303] It therefore parallels the silver inlays along the crest of the Sutton Hoo helmet.[301][670] Such a crest would, as described in Beowulf, provide protection from a falling sword. "A quick turn of the head as the blow fell would enable the wearer to take it across the 'comb' and avoid its falling parallel with the comb and splitting the cap."[520][302]

The discovery has led many Old English dictionaries to define wala within the "immediate context" of Beowulf, including as a "ridge or comb inlaid with wires running on top of helmet from front to back," although doing so "iron[s] out the figurative language" intended in the poem.[667] The specific meaning of the term as used within the poem is nevertheless explicated by the Sutton Hoo helmet, in turn "illustrat[ing] the intimacy of the relationship between the archaeological material in the Sutton Hoo grave and the Beowulf poem."[520][671]

A final parallel between the Sutton Hoo helmet and those in Beowulf is the presence of face masks, a feature which makes the former unique among its Anglo-Saxon and East Scandinavian counterparts.[672][282][300] The uniqueness may reflect that, as part of a royal burial,[300] the helmet is "richer and of higher quality than any other helmet yet found."[409] In Beowulf, "a poem about kings and nobles, in which the common people hardly appear,"[330] compounds such as "battle-mask" (beadogriman[673]), "war-mask" (heregriman[674]), "mask-helm" (grimhelmas[675]), and "war-head" (wigheafolan[676]) indicate the use of visored helmets.[677][678] The term "war-head" is particularly apt for the anthropomorphic Sutton Hoo helmet. "[T]he word does indeed describe a helmet realistically. Wigheafola: complete head-covering, forehead, eyebrows, eye-holes, cheeks, nose, mouth, chin, even a moustache!"[679]

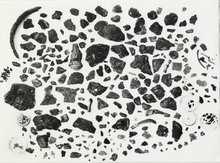

Discovery[edit]

The Sutton Hoo helmet was discovered over three days in July and August 1939, with only three weeks remaining in the excavation of the ship-burial. It was found in more than 500 pieces,[680] which would prove to account for less than half of the original surface area.[12] The discovery was recorded in the diary of C. W. Phillips as follows:

Friday, 28 July 1939: "The crushed remains of an iron helmet were found four feet [1.2 m] east of the shield boss on the north side of the central deposit. The remains consisted of many fragments of iron covered with embossed ornament of an interlace with which were also associated gold leaf, textiles, an anthropomorphic face-piece consisting of a nose, mouth, and moustache cast as a whole (bronze), and bronze zoomorphic mountings and enrichments."

Saturday, 29 July: "A few more fragments of the iron helmet came to light and were boxed with the rest found the day before."

Tuesday, 1 August: "The day was spent in clearing out the excavated stern part of the ship and preparing it for study. Before this a final glean and sift in the burial area had produced a few fragments which are probably to be associated with the helmet and the chain mail respectively."[681][13]

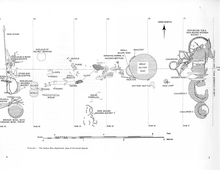

Although the helmet is now considered to be one of the most important artefacts ever found on British soil,[12][684] its shattered state caused it to go at first unnoticed. No photographs were taken of the fragments in situ, nor were their relative positions recorded,[12][11][13] as the importance of the discovery had not yet been realised.[126][note 24] The only contemporary record of the helmet's location was a circle on the excavation diagram marked "nucleus of helmet remains."[682][683] When reconstruction of the helmet commenced years later, it would thus become "a jigsaw puzzle without any sort of picture on the lid of the box,"[12][11] not to mention a jigsaw puzzle missing half its pieces.

Overlooked at first, the helmet quickly gained notice. Even before all the fragments had been excavated, the Daily Mail spoke of "a gold helmet encrusted with precious stones."[686] A few days later it would more accurately describe the helmet as having "elaborate interlaced ornaments in silver and gold leaf."[687] Despite scant time to examine the fragments,[688][689] they were termed "elaborate"[690] and "magnificent";[691] "crushed and rotted"[692] and "sadly broken" such that it "may never make such an imposing exhibit as it ought to do,"[693] it was nonetheless thought the helmet "may be one of the most exciting finds."[692] The stag found in the burial—later placed atop the sceptre—was even thought at first to adorn the crest of the helmet.[694][693][695][696][697]

Donation[edit]

Under the common law in effect at the time, gold and silver that had been hidden and later rediscovered, with the original ownership undetermined, was declared treasure trove, and thus the property of the crown.[note 25] As defined by William Blackstone in Commentaries on the Laws of England, treasure trove "is where any money or coin, gold, silver, plate, or bullion, is found hidden in the earth, or other private plate, the owner thereof being unknown; in which case the treasure belongs to the king: but if he that hid it be known, or afterwards found out, the owner and not the king is entitled to it. Also if it be found in the sea, or upon the earth, it doth not belong to the king, but the finder, if no owner appears. So that it seems it is the hiding, not the abandoning of it, that gives the king a property".[698][699] Those who discovered such treasure were obliged to report their finds to a county coroner,[700] after which an inquest would be held to determine the rightful owner.[701]

Items with only marginal amounts of gold or silver, such as the Sutton Hoo helmet, were not eligible for treasure trove; instead, they became the property of the landowner, Edith Pretty, outright.[702][703][704] An inquest for the remaining items, comprising 56 categories of objects, was held on 14 August 1939.[705][706][707] The 14-person jury found that the objects did not constitute treasure trove, and thus belonged to Pretty; the dispositive issue was that, as the coroner put it, given "the labour and publicity involved in dragging the ship up to the trench", presumably accompanied by "attendant publicity and subsequent feasting", it was "impossible to be of the opinion that these articles were buried or concealed secretly".[708][709][note 26] Within days, however, Pretty donated the entirety of the find to the British Museum.[713][714] Even had the gold and silver objects been declared treasure trove, ownership of the remaining objects, including the helmet, would have remained with Pretty; donation was thus one of the sole vehicles by which the museum could have taken possession of the finds.[702][703][704]

Excavations at Sutton Hoo came to an end on 24 August 1939, and all items were shipped out the following day.[715] Nine days later, Britain declared war on Germany. The intervening time allowed for fragile and perishable objects to be tended to, and for the finds to be secured for safekeeping.[716] Throughout World War II the Sutton Hoo artefacts, along with other treasures from the British Museum such as the Elgin Marbles,[717][718] were stored in the tunnel connecting the Aldwych and Holborn tube stations.[719][684] Only at the end of 1944 were preparations made to unpack, conserve and restore the finds from Sutton Hoo.[227]

First reconstruction[edit]

The helmet was first reconstructed by Herbert Maryon between 1945 and 1946.[720][721] A retired professor of sculpture and an authority on early metalwork, Maryon was specially employed as a Technical Attaché at the British Museum on 11 November 1944.[722] His job was to restore and conserve the finds from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial, including what Bruce-Mitford called "the real headaches – notably the crushed shield, helmet and drinking horns".[227]

Maryon's work on the Sutton Hoo objects continued until 1950,[723][724] of which six continuous months were spent reconstructing the helmet.[725] This reached Maryon's workbench as a corroded mass of fragments, some friable and encrusted in sand, others hard and partially transformed into limonite.[726] As Bruce-Mitford observed, the "task of restoration was thus reduced to a jigsaw puzzle without any sort of picture on the lid of the box,"[12] and, "as it proved, a great many of the pieces missing."[129]

Maryon began by familiarising himself with the various fragments;[126][727] he traced and detailed each one on a piece of stiff paper,[126] and segregated them by decorations, distinctive markings, and thickness.[728] After what he termed "a long while", Maryon turned to reconstruction.[126] He adhered the adjoining pieces with Durofix, holding them together in a box of sand while the adhesive hardened.[728] These were then placed on a human-sized head Maryon sculpted from plaster, with added layers to account for the lining that would have originally separated head from metal.[215]

The fragments of the skull cap were initially stuck to the head with Plasticine, or, if thicker, placed into spaces cut into the head. Finally, strong white plaster was used to permanently affix the fragments, and, mixed with brown umber, fill in the gaps between pieces.[215] Meanwhile, the fragments of the cheek guards, neck guard, and visor were placed onto shaped, plaster-covered wire mesh, then affixed with more plaster and joined to the cap.[729]

Though visibly different from the current reconstruction, Bruce-Mitford wrote, "[m]uch of Maryon's work is valid. The general character of the helmet was made plain."[136] The 1946 reconstruction identified the designs recognised today, and similarly arranged them in a panelled configuration.[169] Both reconstructions composed the visor and neck guards with the same designs: the visor with the smaller interlace (design 5), the neck guard with a top row of the larger interlace (design 4) above two rows of the smaller interlace.[730][731][732][250] The layout of the cheek guards is also similar in both reconstructions; the main differences are the added length provided by a third row in the second reconstruction, the replacement of a design 4 panel with the dancing warriors (design 1) in the middle row, and the switching of sides.[730][731][732][250]

Reception and criticism[edit]

The first reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet was met with worldwide acclaim and was both academically and culturally influential.[733] It stayed on display for more than 20 years,[136][733] during which time it became an iconic object of the Middle Ages.[136][734][735] In 1951 the helmet was displayed at the Festival of Britain,[736] where an exhibit on Sutton Hoo was curated by Rupert Bruce-Mitford.[737] That same year Life dispatched a 25-year-old Larry Burrows to the British Museum, resulting in a full-page photograph of the helmet alongside a photograph of Maryon.[738][739] In 1956, on the strength of his restorations, Maryon was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.[740][741][742]

Images of the helmet made their way into television programmes,[743] books, and newspapers,[744][745] even as the second reconstruction was worked on.[746] Though the lasting impact of the first reconstruction is as a first, reversible, attempt from which problems could be identified and solutions found,[747][742] for two decades Maryon's reconstruction was an icon in its own right.[136][734][735]

With the helmet on public display and as greater knowledge of contemporary helmets became available,[748] the first reconstruction, Bruce-Mitford wrote, "was soon criticised, though not in print, by Swedish scholars and others."[12][749][note 27] An underlying issue was the decision to arrange the fragments around the mould of an average man's head, possibly inadvertently predetermining the reconstruction's size.[669][752] Particular criticisms also noted its exposed areas, and a neck guard that was fixed rather than movable.[753][754][733]

Though envisioned by Maryon as similar to a "crash helmet of a motor cyclist" with padding of about 3⁄8 inch (9.5 mm) between head and helmet,[126] its size allowed for little such cushioning;[752][669][733] one with a larger head would have had difficulty just getting it on.[733] The missing portion at the front of each cheek piece left the jaw exposed,[752][755] there was a hole between eyebrows and nose, and the eye holes were large enough for a sword to pass through.[733] Meanwhile, as noted early on by Sune Lindqvist,[750] the projecting face mask seemed odd, and would have left the wearer's nose vulnerable to blows to the face.[733]

An artistic reconstruction created in 1966 by the British Museum and the Archaeology Division of the Ordnance Survey, under the direction of C. W. Phillips,[756][757] attempted to solve some of these problems, showing a larger cap, a straighter face mask, smaller eye openings, the terminal dragon heads at opposite ends, and the rearrangement of some of the pressblech panels.[758] It too, however, came under criticism by archaeologists.[759]