Kunyu Wanguo Quantu

| Kunyu Wanguo Quantu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 坤輿萬國全圖 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 坤舆万国全图 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | A Map of the Myriad Countries of the World | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

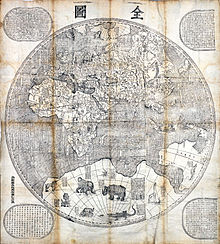

Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, printed in Ming China at the request of the Wanli Emperor in 1602 by the Italian Catholic missionary Matteo Ricci and Chinese collaborators, the mandarin Zhong Wentao, and the technical translator Li Zhizao, is the earliest known Chinese world map with the style of European maps.[1] It has been referred to as the Impossible Black Tulip of Cartography, "because of its rarity, importance and exoticism".[2] The map was crucial in expanding Chinese knowledge of the world. It was eventually exported to Korea[3] then Japan and was influential there as well,[4] though less so than Giulio Aleni's Zhifang Waiji.

Description[edit]

The 1602 Ricci map is a very large, 5 ft (1.52 m) high and 12 ft (3.66 m) wide, woodcut using a pseudocylindrical map projection showing China at the center of the known world.[2] It is the first map in Chinese to show the Americas. The map's mirror image originally was carved on six large blocks of wood and then printed in brownish ink on six mulberry paper panels, similar to the making of a folding screen.

It portrays both North and South America and the Pacific Ocean with reasonable accuracy. China appropriately is linked to Asia, India, and the Middle East. Europe, the Mediterranean, and Africa also are well delineated.[2] Diane Neimann, a trustee of the James Ford Bell Trust, notes that: "There is some distortion, but what's on the map is the result of commerce, trade and exploration, so one has a good sense of what was known then."[2]

Ti Bin Zhang, first secretary for cultural affairs at the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., said in 2009: "The map represents the momentous first meeting of East and West" and was the "catalyst for commerce."[5]

Details[edit]

The map includes images and annotations describing different regions of the world. Africa is noted to have the world's highest mountain and longest river. The brief description of North America mentions "humped oxen" or bison (駝峰牛 tuófēngníu), feral horses (野馬, yěmǎ), and names Canada (加拿大, Jiānádà). The map identifies Florida as Huādì (花地), the "Land of Flowers." Several Central and South American places are named, including Guatemala (哇的麻剌, Wādemálá), Yucatan (宇革堂, Yǔgétáng), and Chile (智里, Zhīlǐ).[5]

The map's cartographer, Matteo Ricci, gave a brief description of the discovery of the Americas. "In olden days, nobody had ever known that there were such places as North and South America or Magellanica (using a name that early mapmakers gave to a supposed continent including Australia, Antarctica, and Tierra del Fuego), but a hundred years ago, Europeans came sailing in their ships to parts of the sea coast, and so discovered them."[5]

The Museo della Specola Bologna has in its collection, displayed on the wall of the Globe Room, original copies of panels 1 and 6 of the six panels comprising the 1602 Ricci map. During restoration and mounting, a central panel—a part of the Doppio Emisfero delle Stelle by the German mathematician and astronomer Johann Adam Schall von Bell—was inserted between the two sections by mistake.

In 1958, Pasquale D’Elia, sinologist at the University of Rome certified the authenticity of the Chinese maps in this museum’s possession, (see op. cit.) stating that "it is the third edition of a geographical and cartographical work that made Ricci famous throughout China. He had already made a first edition in 1584 at Shiuhing, followed by a second in 1600 at Nanking, and two years later a third in Peking.[6]

In 1938, an exhaustive work by Pasquale d'Elia, edited by the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, was published with comments, notes, and translation of the whole map.[7] The maps carry plentiful instructions for use and detailed illustrations of the instruments that went into their production, as well as explanations regarding conceptions of "systems of the terrestrial and celestial world".[6] There is a long preface by Matteo Ricci in the middle of the map, where it depicts the Pacific Ocean. D’Elia’s translation reads:

"Once I thought learning was a multifold experience and I would not refuse to travel [even] ten thousand Li to be able to question wise men and visit celebrated countries. But how long is a man’s life? It is certain that many years are needed to acquire a complete science, based on a vast number of observations: and that’s where one becomes old without the time to make use of this science. Is this not a painful thing?

And this is why I put great store by [geographical] maps and history: history for fixing [these observations], and maps for handing them on [to future generations].

Respectfully written by the European Matteo Ricci on 17 August 1602."

The figure of the Nove Cieli (Nine Skies) is printed to the left of the title, illustrated as per sixteenth-century conceptions. The accompanying inscription explains the movement of the planets. The right-hand section (panel 6) has other inscriptions giving general ideas on geography and oceanography. Another inscription records an extract of the Storia dei Mongoli regarding the motions of the Sun. In the top of the left-hand section (panel 1), there is an explanation of eclipses and the method for measuring the Earth and the Moon. Both sections carry the characteristic Jesuit seal, the IHS of the Society of Jesus. At the bottom left, in the Southern Hemisphere, is the name of the Chinese publisher of the map and the date: one day of the first month of autumn in the year 1602.[6]

The map also incorporates an explanation of parallels and meridians, a proof that the Sun is larger than the Moon, a table showing the distances of planets from the Earth, an explanation of the varying lengths of days and nights, and polar projections of the Earth that are unusually consistent with its main map.[8]

History[edit]

Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) was a Jesuit priest. Ricci was one of the first Western scholars to live in China and he became a master of Chinese script and Classical Chinese. In 1583, Ricci was among the first Jesuits to enter China from Macao. The first Chinese world map was named Yudi Shanhai Quantu (輿地山海全圖) and made in Zhaoqing in 1584 by Matteo Ricci with Chinese collaborators.[9] Ricci had a small Italian wall map in his possession and created Chinese versions of it at the request of the governor of Zhaoqing at the time, Wang Pan, who wanted the document to serve as a resource for explorers and scholars.[10]

On January 24, 1601, Ricci was the first Jesuit - and one of the first Westerners - to enter the Ming capital Beijing,[6] bringing atlases of Europe and the West that were unknown to his hosts. The Chinese had maps of the East that were equally unfamiliar to Western scholars.

In 1602, at the request of the Wanli Emperor, Ricci collaborated with Mandarin Zhong Wentao, a technical translator, Li Zhizao,[9] and other Chinese scholars in Beijing to create what was his third and largest world map, the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu.[10]

In this map, European geographic knowledge, new to the Chinese, was combined with Chinese information unknown to Europeans to create the first map known to combine Chinese and European cartography.[10] Among other things, this map revealed the existence of America to the Chinese. Ford W. Bell said: "This was a great collaboration between East and West. It really is a very clear example of how trade was a driving force behind the spread of civilization."

According to John D. Day,[11] Matteo Ricci prepared four editions of Chinese world maps during his mission in China before 1603:

- a 1584 early woodblock print made in Zhaoqing, called Yudi Shanhai Quantu;

- a 1596 map carved on a stele, called Shanhai Yudi Tu (山海輿地圖);

- a 1600 revised version of the 1596, usually named Shanhai Yudi Quantu (山海輿地全圖), engraved by Wu Zhongming;

- a 1602 larger and much refined edition of the 1584 map, in six panels, printed in Beijing, called Kunyu Wanguo Quantu;[11][12][13][14]

Several prints of the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu were made in 1602. Most of the original maps now are lost. Only six original copies of the map are known to exist, and only two are in good condition. Known copies are in the Vatican Apostolic Library Collection I and at the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota. The Vatican's 1602 copy was reproduced by Pasquale d’Elia in the beautifully arranged book, Il mappamondo cinese del P Matteo Ricci, S.I. in 1938. This modern work also contains Italian translations of the colophons on the map, a catalogue of all toponyms, plus detailed notes regarding their identification.[11][15]

Other copies of the 1602 map are located at: Japan, Kyoto University Collection; collection of Japan Miyagi Prefecture Library; Collection of the Library of the Japanese Cabinet; and a private collection in Paris, France.[2][10] No original examples of the map are known to exist in China, where Ricci was revered and buried.[5]

The maps received widespread attention and circulation. The governor General of Guizhou reproduced a copy of the map in a book about Guizhou published in Guiyang in 1604. Ricci estimated that more than 1,000 copies of the 1602 edition were reprinted.[16]

Various versions of the map were exported to Korea and later Japan. The first Korean copy was brought back from Beijing by visiting ambassadors in 1603.[3] An unattributed and very detailed two page coloured edition of the map, known in Japanese as Konyo Bankoku Zenzu, was made in Japan circa 1604. Within this Japanese export copy, Japanese Katakana is utilised for foreign location names throughout the Western world.

The Gonyeomangukjeondo (Hangul: 곤여만국전도) is a Korean hand-copied reproduction print by Painter Kim Jin-yeo in 1708, the 34th year of King Sukjong's rule of Joseon. It is 533×170 cm, on mulberry paper. This map was brought to Korea in 1710 by Lee Gwan-jeong and Gwon Hui, two envoys of Joseon to China. It is owned and displayed at Seoul National University Museum, and is a National Treasure. The map shows five world continents and over 850 toponyms. It contains descriptions of ethnic groups and main products associated with each region. In the margins outside the ellipse, there are images of the northern and southern hemispheres, the Aristotelian geocentric world system, and the orbits of the Sun and Moon. It has an introduction by Choe Seok-jeong providing information on the constitution of the map and its production process.[17]

Bell Library copy[edit]

The James Ford Bell Trust announced in December 2009 that it had acquired one of two good copies of the 1602 Ricci map from the firm of Bernard J. Shapero, a noted dealer of rare books and maps in London, for US$1 million, the second most expensive map purchase in history. This copy had been held for years by a private collector in Japan.[5]

Ford W. Bell, president of the American Association of Museums (now the American Alliance of Museums) and a trustee of the James Ford Bell Trust started by his grandfather, James Ford Bell, the founder of General Mills, said in an interview with a reporter from Minnesota Public Radio's All Things Considered: "These opportunities don't present themselves very often. This map was the only one on the market, and the only one likely to be on the market. So we had to take advantage of that opportunity."[1]

The map was displayed for the first time in North America at the Library of Congress from January through April, 2010. It was scanned by the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division to create a permanent digital image that will be posted on the internet later in 2010 in the World Digital Library for scholars and students to study. The map was then exhibited briefly at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, before moving to its permanent home at the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota, where it has been on display since September 15, 2010.[1][18]

Chinese maps published after 1602[edit]

Before his death at Peking in 1610, Matteo Ricci prepared four more world maps after the 1602 one:

- 5. a 1603 eight panel version of the 1602 map, usually named Liangyi Xuanlan Tu (兩儀玄覽圖) (Map for the far-reaching observation of heaven and earth). The 1603 edition is larger than the 1602, but is less well known because of the fewer extant copies and versions based on it;[19]

- 6. a 1604 booklet based on the map of 1600, also named Shanhai Yudi Quantu; engraved by Guo Zizhang (郭子章);

- 7. a new 1608 version, twelve copies presented to the emperor

- 8. and a 1609 map in two hemispheres.[11]

Most of these maps now are lost. Later copies of the 1602 edition of the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu may be found in China, Korea, London, and Vienna;[20] one copy of the map recently was discovered in the store-rooms of the Shenyang Museum in China. A world search is currently in progress by Kendall Whaling Museum of Massachusetts.[6] Hong Weilian,[13] earlier established a list of twelve total Ricci maps, which differs considerably from Day’s findings.[14]

In 1607 or 1609 the Shanhai Yudi Quantu, is a Chinese map which was published in the geographical treatise Sancai Tuhui. The Shanhai Yudi Quantu was influenced highly by the work of Matteo Ricci.[21] Matteo Ricci had several of his own maps entitled Shanhai Yudi Quantu.[22] The locations in the map have been identified and translated by Roderich Ptak in his work, The Sino-European Map (“Shanhai yudi quantu”), in the Encyclopedia Sancai tuhui:[14]

About 1620 Giulio Aleni made the world map Wanguo Quantu (萬國全圖, lit. "Complete map of all the countries"), putting China at the center of the world map, following Ricci's format and contents, but in a much smaller size (49 cm x 24 cm). This map was included in some editions of Aleni's geographical work, Zhifang waiji. (Descriptions of Foreign Land) His 1623 preface states that another Jesuit, Diego de Pantoja (1571–1618), on the command of the emperor, had translated a different European map, also following Ricci's model, but there is no other knowledge of that work.[19]

In 1633, the Jesuit, Francesco Sambiasi (1582–1649), composed and annotated another world map, entitled Kunyu Quantu (Universal Map of the World), in Nanjing.

In 1674, Ferdinand Verbiest developed the Kunyu Quantu, a similar map, but with various improvements.[24] It consists of eight panels, each 179 cm x 54 cm, together displaying two hemispheres in Mercator projection. The two outer scrolls individually depict cartouches that contain several kinds of information on geography and meteorology. The making of Verbiest's Kunyu Quantu was intended to meet the interest of the Kangxi Emperor, as Verbiest's introductory dedication implies. There currently are at least fourteen or fifteen copies and editions of this map known in Europe, Japan, Taiwan, America, and Australia.[19]

Religious significance[edit]

Ricci was a Jesuit priest whose mission was to convert the Chinese to Roman Catholicism. He thought that might be helped by demonstrating the superior understanding of the world that he believed grew out of Christian faith. The map’s text shows it as part of a diplomatic attempt by Ricci to affirm the greatness of his own religion and culture. Ricci declares that it offers testimony “to the supreme goodness, greatness and unity of Him who controls heaven and earth.”[8]

Gallery[edit]

-

Unknown edition or poor copy of 1602 Ricci map

-

1620s Wanguo Quantu map, by Giulio Aleni, whose Chinese name (艾儒略) appears in the signature in the last column on the left, above the Jesuit IHS symbol.[25]

-

1602 Ricci map - detail of Gulf of Mexico, Florida, Cuba, Yucatan, Mexico

-

1602 Ricci map - detail from a China panel

-

1602 Ricci map - detail of North and Central America

-

Detail of China and Far East, from the 1604 copy

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Baran, Madeleine (December 16, 2009). "Historic map coming to Minnesota". St. Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Abbe, Mary (2009-12-18). "Million-dollar map coming to Minnesota". Star Tribune. Minneapolis: Star Tribune Company. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ a b Park, Seongrae (2000), "The Introduction of Western Science in Korea: A Comparative View with the Cases of China and Japan" (PDF), Northeast Asian Studies, vol. 4, p. 32.

- ^ Japan and China: mutual representations in the modern era Wataru Masuda p.17 [1]

- ^ a b c d e "Rare map puts China at centre of world". CBC News. Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Centre. 12 January 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Battistini, Pierluigi (1997-08-26). "65. Geographical map by Matteo Ricci". Museo della Specola, Catalogue, maps. Bologna: University of Bologna. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ^ d' Elia, Pasquale M. (1938). Il mappamondo cinese del P Matteo Ricci, S.I. (3. ed., Pechino, 1602) conservato presso la Biblioteca Vaticana, commentato tradotto e annotato dal p. Pasquale M. d'Elia, S. I. ... Con XXX tavole geografiche e 16 illustrazioni fuori testo ... Vatican: Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca apostolica Vaticana. OCLC 84361232. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ^ a b Rothstein, Edward (2010-01-19). "Map That Shrank the World". New York Times, Arts, Exhibition Review. New York: The New York Times Company. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ a b Elman, Benjamin A. (April 2005). "Sin0-Jesuit Accommodations During the Seventeenth Century". On their own terms: science in China, 1550–1900. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 127-Matteo Mundi's Mappa Mundi. ISBN 978-0-674-01685-9.

- ^ a b c d "The James Ford Bell Library to Unveil Ricci Map on January 12". James Ford Bell Library. Minneapolis: Regents of the University of Minnesota. 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d John D. Day, “The Search for the Origins of the Chinese Manuscripts of Matteo Ricci’s Maps”, Imago Mundi 47 (1995), pp. 94–117

- ^ Hong Weilian, earlier established a list of twelve total Ricci maps, which differs from Day’s findings.

- ^ a b “Kao Li Madou de shijie ditu”, p. 28

- ^ a b c Ptak, Roderich (2005). "The Sino-European Map ("Shanhai yudi quantu") in the Encyclopedia Sancai tuhui" (PDF). Humanismo Latino: 1–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-21. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Mappamondo. For earlier English translations of some of the colophons, see, for example, Lionel Giles, “Translations from the Chinese World Map of Father Ricci”, Geographical Journal 52 (1918), pp. 367–385; and 53 (1919), pp. 19–30.

- ^ Hostetler, Laura (2001). "Two- Mapping Territory". Qing Colonial Enterprise: Ethnography and Cartography in Early Modern China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 52–54. ISBN 978-0-226-35420-0. OCLC 61477717.

- ^ "Gonyeomangukjeondo (Kunyu Wanguo Quantu; Complete Map of the World)". Cultural History of Seoul. Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ Urschel, Donna (12 January 2010). "Rare 1602 World Map, the First Map in Chinese to Show the Americas, on Display at Library of Congress, Jan. 12 to April 10". News from the Library of Congress. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ a b c Chen, Hui-hung (July 2007). "The Human Body as a Universe: Understanding Heaven by Visualization and Sensibility in Jesuit Cartography in China". The Catholic Historical Review. 93 (3). The Catholic University of America Press: 517–552. doi:10.1353/cat.2007.0236. ISSN 0008-8080. S2CID 56440788.

- ^ A reproduction of the Vienna map can be found in Österreichisch Nationalbibliothek (1995).Kartographische Zimelien. Die 50 schönsten Karten und Globen der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. Wien: Holzhausen.

- ^ Ptak, p.1

- ^ Ptak, p.3

- ^ Wigal, p.202

- ^ Verbiest, Ferdinand (1674). "KUNYU QUANTU (A Map of the Whole World)". Museum's Gateway. Melbourne: University of Melbourne, Universitas 21. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Vatican exhibit

Further reading[edit]

- Ch'en, Kenneth; Ricci, Matteo (1939). "Matteo Ricci's Contribution to, and Influence on, Geographical Knowledge in China". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 59 (3): 325–359. doi:10.2307/594690. ISSN 0003-0279.

- Day, John D. (1995). "The Search for the Origins of the Chinese Manuscript of Matteo Ricci's Maps". Imago Mundi. 47: 94–117. ISSN 0308-5694.

- Needham, Joseph (1959). "Chapter 22 - Geography and Cartography". Science And Civilisation In China, Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. pp. 497–590.

- Yee, Cordell D.K. (1994). "Chapter 7 - Traditional Chinese Cartography and the Myth of Westernization" (PDF). In Woodward, David (ed.). The History of Cartography, Volume Two, Book Two. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 170–200.

External links[edit]

- The "Great Universal Geographic Map" at the World Digital Library.

- "Opere Di Matteo Ricci[permanent dead link]" ["The works of Matteo Ricci"], including descriptions of the six editions of Ricci's world map, by Alfredo Maulo (in Italian)

- Audio – MPR's Tom Crann talks with Ford W. Bell about Matteo Ricci and the first Chinese world map

- Museo della Specola

- Bernard J. Shapero

- Interview with Ann Waltner about map

![1620s Wanguo Quantu map, by Giulio Aleni, whose Chinese name (艾儒略) appears in the signature in the last column on the left, above the Jesuit IHS symbol.[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Wanguo_Quantu.jpg/120px-Wanguo_Quantu.jpg)