Internet GIS

Internet GIS, or Internet geographic information system (GIS), is a term that refers to a broad set of technologies and applications that employ the Internet to access, analyze, visualize, and distribute spatial data.[1][2][3][4][5] Internet GIS is an outgrowth of traditional GIS, and represents a shift from conducting GIS on an individual computer to working with remotely distributed data and functions.[1] Two major issues in GIS are accessing and distributing spatial data and GIS outputs.[6] Internet GIS helps to solve that problem by allowing users to access vast databases impossible to store on a single desktop computer, and by allowing rapid dissemination of both maps and raw data to others.[7][6] These methods include both file sharing and email. This has enabled the general public to participate in map creation and make use of GIS technology.[8][9]

Internet GIS is a subset of Distributed GIS, but specifically uses the internet rather than generic computer networks. Internet GIS applications are often, but not exclusively, conducted through the World Wide Web (also known as the Web), giving rise to the sub-branch of Web GIS, often used interchangeably with Internet GIS.[10][11][12][4][5] While Web GIS has become nearly synonymous with Internet GIS to many in the industry, the two are as distinct as the internet is from the World Wide Web.[13][14][15] Likewise, Internet GIS is as distinct from distributed GIS as the Internet is from distributed computer networks in general.[1][4][5]

Internet GIS includes services beyond those enabled by the Web. Use of any other internet-enabled services to facilitate GIS functions, even if used in conjuncture with the Web, represents the use of Internet GIS.[4][5] One of the most common applications of a distributed GIS system, accessing remotely saved data, can be done through the internet without the need for the Web.[4][5] This is often done in practice when data are sensitive, such as hospital patient data and research facilities proprietary data, where sending data through the Web may be a security risk. This can be done using a Virtual private network (VPN) to access a local network remotely.[16] The use of VPN for these purposes surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, when employers needed to allow employees using GIS access to sensitive spatial data from home.[17][18][19]

History[edit]

The history of Internet geographic information systems is linked to the history of the computer, the internet, and the quantitative revolution in geography. Geography tends to adapt technologies from other disciplines rather than innovating and inventing the technologies employed to conduct geographic studies.[20] The computer and internet are not an exception, and were rapidly investigated to purpose towards the needs of geographers. In 1959, Waldo Tobler published the first paper detailing the use of computers in map creation.[21] This was the beginning of computer cartography, or the use of computers to create maps.[22][23] In 1960, the first true geographic information system capable of storing, analyzing, changing, and creating visualizations with spatial data was created by Roger Tomlinson on behalf of the Canadian Government to manage natural resources.[24][25] These technologies represented a paradigm shift in cartography and geography, with desktop computer cartography facilitated through GIS rapidly replaced traditional ways of making maps.[20] The emergence of GIS and computer technology contributed to the quantitative revolution in geography and the emergence of the branch of technical geography.[26][27]

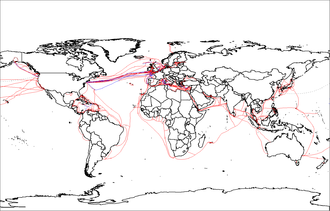

As computer technology advanced the desktop machine became the default for producing maps, a process known as digital mapping, or computer cartography. These computers were networked together to share data and processing power and create redundant communications for defense applications.[12] This computer network evolved into the internet, and by the late 1980s, the internet was available in some people's homes.[12] Over time, the internet moved from a novelty to a major part of daily life. Using the internet, it was no longer necessary to store all data for a project locally, and communications were vastly improved. Following this trend, GIScientists began developing methods for combining the internet and GIS. This process accelerated in the 1990s, with the creation of the World Wide Web in 1990 and the first major web mapping program, Xerox PARC Map Viewer, capable of distributed map creation appearing in 1993.[12][28][9] This software was unique in that it facilitated dynamic user map generation, rather than static images.[28] These new Web-based programs helped users to employ GIS without having it locally installed on their machine, ultimately leading to Web GIS being the dominant way users interact with internet GIS.[10][28]

In 1995 The US federal government made the TIGER Mapping Service available to the public, facilitating desktop and Web GIS by hosting US boundary data.[10] This data availability, facilitated through the internet, silently revolutionized cartography by providing the world with authoritative boundary files, for free. In 1996, MapQuest became available to the public, facilitating navigation and trip planning.[10] Sometime during the 1990s, more maps were transmitted over the internet than physically printed.[12] This milestone was predicted in 1985 and represented a major shift in how we distribute spatial products to the masses.[29]

As of 2020, almost 75% of the population has a smartphones.[1][30] These devices allow users to access the internet wherever they have service, and have revolutionized how we interact with the internet. One notable example is the rise of mobile apps, which have impacted both how GIS is done, and how data are collected. Some mobile apps like the Google Maps mobile app are web-based and allow users to get navigation instructions in real time. Others, like Esri's Survey123 allow users to collect data in the field with their smartphone.[31] As time progresses, internet-based applications that do not make use of HTML or Web Browsers have begun to become to grow in popularity.[32]

Web GIS[edit]

The World Wide Web is an information system that uses the internet to host, share, and distribute documents, images, and other data.[33] Web GIS involves using the World Wide Web to facilitate GIS tasks traditionally done on a desktop computer, as well as enabling the sharing of maps and spatial data.[7] Most, but not all, internet GIS is Web GIS, however all Web GIS is internet GIS.[10][11] This is quite similar to how much of the activity on the internet is hosted on the World Wide Web, but not everything on the internet is the World Wide Web. The tasks Web GIS are used for are numerous but can be generally divided into the categories of Geospatial web services: web feature services, web processing services, and web mapping services.[3]

Criticism[edit]

By their definition, maps can never be perfect and are simplifications of reality.[34] Ethical cartographers try to keep these inaccuracies documented and to a minimum, while encouraging critical perspectives when using a map. Internet GIS has brought map-making tools to the general public, facilitating the rapidly disseminating these maps.[35] While this is potentially positive, it also means that people without cartographic training can easily make and disseminate misleading maps to a wide audience.[20][36][37] This was brought to public attention during the COVID-19 pandemic, when more than half of all United States state government COVID-19 dashboards had cartographic errors.[38] Further, malicious actors can quickly spread intentionally misleading spatial information while hiding the source.[34] As the internet is decentralized, traditional solutions to problems such as government regulation are difficult or impossible to implement.[39]

For many users, the World Wide Web is synonymous with the Internet, which is true for Internet GIS. Most functions done with Internet GIS are conducted through the use of Web GIS. This has caused the borders between the two terms to blur, and "Web GIS" to become genericized into meaning any GIS done over the internet to some users.

See also[edit]

- Collaborative mapping

- Comparison of GIS software

- Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

- Digital geologic mapping

- Geodatabase (Esri)

- GIS Day

- Historical GIS

- List of GIS data sources

- List of GIS software

- Local search (Internet)

- Map database management

- Participatory GIS

- Quantitative geography

- Spatial neural network

- Technical geography

- Tobler's first law of geography

- Tobler's second law of geography

- Traditional knowledge GIS

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Peng, Zhong-Ren; Tsou, Ming-Hsiang (2003). Internet GIS: Distributed Information Services for the Internet and Wireless Networks. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-35923-8. OCLC 50447645.

- ^ Moretz, David (2008). "Internet GIS". In Shekhar, Shashi; Xiong, Hui (eds.). Encyclopedia of GIS. New York: Springer. pp. 591–596. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-35973-1_648. ISBN 978-0-387-35973-1. OCLC 233971247.

- ^ a b Zhang, Chuanrong; Zhao, Tian; Li, Weidong (2015). Geospatial Semantic Web. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-17801-1. ISBN 978-3-319-17800-4. OCLC 911032733. S2CID 63154455.

- ^ a b c d e Ezekiel, Kuria; Kimani, Stephen; Mindila, Agnes (June 2019). "A Framework for Web GIS Development: A Review". International Journal of Computer Applications. 178 (16): 6–10. doi:10.5120/ijca2019918863. S2CID 196200139.

- ^ a b c d e Rowland, Alexandra; Folmer, Erwin; Beek, Wouter (2020). "Towards Self-Service GIS—Combining the Best of the Semantic Web and Web GIS". ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 9 (12): 753. doi:10.3390/ijgi9120753.

- ^ a b DeMers, Michael (2009). Fundamentals of Geographic Information Systems (4 ed.). Wiley.

- ^ a b Plewe, Brandon (1997). GIS Online: INFORMATION RETRIEVAL, MAPPING, AND THE INTERNET (1 ed.). OnWord Press. ISBN 1-56690-137-5.

- ^ Hansen, Henning Sten (November 2005). "Citizen participation and Internet GIS—Some recent advances". Computers, Environment and Urban Systems. 29 (6): 617–629. doi:10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2005.07.001. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ a b Plew, Brandon (2007). "Web Cartography in the United States". Cartography and Geographic Information Science. 34 (2): 133–136. doi:10.1559/152304007781002235. S2CID 140717290. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Fu, Pinde; Sun, Jiulin (2011). Web GIS: Principles and Applications. Redlands, Calif.: ESRI Press. ISBN 978-1-58948-245-6. OCLC 587219650.

- ^ a b Fu, Pinde (2016). Getting to Know Web GIS (2 ed.). Redlands, Calif.: ESRI Press. ISBN 9781589484634. OCLC 928643136.

- ^ a b c d e Peterson, Michael P. (2014). Mapping in the Cloud. New York: The Guiford Press. ISBN 978-1-4625-1041-2. OCLC 855580732.

- ^ Mathiyalagan, V.; Grunwald, S.; Reddy, K.R.; Bloom, S.A. (April 2005). "A WebGIS and geodatabase for Florida's wetlands". Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 47 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2004.08.003. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ Veenendaal, Bert; Brovelli, Maria Antonia; Li, Songnian (October 2017). "Review of Web Mapping: Eras, Trends and Directions". ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 6 (10): 317. doi:10.3390/ijgi6100317. hdl:11311/1045866.

- ^ Hojaty, Majid (21 February 2014). "What is the Difference Between Web GIS and Internet GIS?". GIS Lounge. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Maile, McCann; Rob, Watts. "What Is A VPN Used For? 9 VPN Uses In 2022". Forbes Advisor. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ McCarthy, Niall. "VPN Usage Surges During COVID-19 Crisis [Infographic]". Forbes. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Skahill, Jeffrey (April 2020). "Tips for Leading a Remote Team during Covid-19". GIS Lounge. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ "Five Reasons GIS Users Should Use a VPN". gisuser. 4 October 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Monmonier, Mark S. (1985). Technological Transition in Cartography. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299100707. OCLC 11399821.

- ^ Tobler, Waldo (1959). "Automation and Cartography". Geographical Review. 49 (4): 526–534. doi:10.2307/212211. JSTOR 212211. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Clark, Keith (1995). Analytic and Computer Cartography. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0133419002.

- ^ Monmonier, Mark (1982). Computer-Assisted Cartography: Principles and Prospects 1st Edition (1 ed.). Pearson College Div. ISBN 9780131653085.

- ^ "History of GIS | Early History and the Future of GIS - Esri". www.esri.com. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Roger Tomlinson". UCGIS. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Haidu, Ionel (2016). "What is Technical Geography – a letter from the editor". Geographia Technica. 11: 1–5. doi:10.21163/GT_2016.111.01.

- ^ Ormeling, Ferjan (2009). Technical Geography Core concepts in the mapping sciences. p. 482. ISBN 978-1-84826-960-6.

- ^ a b c Putz, Steve (November 1994). "Interactive information services using World-Wide Web hypertext". Computer Networks and ISDN Systems. 27 (2): 273–280. doi:10.1016/0169-7552(94)90141-4. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Monmonier, Mark (1985). Technological Transition in Cartography (1 ed.). Univ of Wisconsin Pr. ISBN 978-0299100704.

- ^ "Topic: Smartphones".

- ^ ESRI. "ArcGIS Survey123". Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ Anderson, Christopher M.; Wolff, Michael J. (September 9, 2010). "The web is dead. Long live the Internet". Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ "What is the difference between the Web and the Internet?". W3C Help and FAQ. W3C. 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ a b Monmonier, Mark (10 April 2018). How to lie with maps (3 ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226435923.

- ^ Monmonier, Mark (1 June 1990). "Ethics and Map Design: Six Strategies for Confronting the Traditional One-Map Solution". Cartographic Perspectives. 1 (10): 3–8. doi:10.14714/CP10.1052. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Adams, Aaron; Chen, Xiang; Li, Weidong; Zhang, Chuanrong (2020). "The disguised pandemic: the importance of data normalization in COVID-19 web mapping". Public Health. 183: 36–37. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.034. PMC 7203028. PMID 32416476.

- ^ Zhong-Ren, Ren (November 2001). "Internet GIS for public participation". Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. 8 (6): 889–905. doi:10.1068/b2750t. S2CID 15012889.

- ^ Adams, Aaron M.; Chen, Xiang; Li, Weidong; Chuanrong, Zhang (27 July 2023). "Normalizing the pandemic: exploring thecartographic issues in state government COVID-19 dashboards". Journal of Maps. 19 (5): 1–9. doi:10.1080/17445647.2023.2235385.

- ^ Peterson, Michael (2008). "Maps and the Internet:What a Mess It Is and How To Fix It". Cartographic Perspectives. 59 (59): 4–11. doi:10.14714/CP59.244. Retrieved 20 January 2024.