History of Marseille

Marseille, France was originally founded circa 600 BC as the Greek colony of Massalia (Latin: Massilia) and populated by Greeks from Phocaea (modern Foça, Turkey). It became the preeminent Greek polis in the Hellenized region of southern Gaul.[1] The city-state allied with the Roman Republic against Carthage during the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), retaining its independence and commercial empire throughout the western Mediterranean even as Rome expanded into Western Europe and North Africa. However, the city lost its independence following the Roman Siege of Massilia in 49 BC, during Caesar's Civil War, in which Massalia sided with the exiled faction at war with Julius Caesar.

Marseille continued to prosper as a Roman city, becoming an early center of Christianity during the Western Roman Empire. The city maintained its position as a premier maritime trading hub even after its capture by the Visigoths in the 5th century AD, although the city went into decline following the sack of 739 AD by the forces of Charles Martel. It became part of the County of Provence during the 10th century, although its renewed prosperity was curtailed by the Black Death of the 14th century and sack of the city by the Crown of Aragon in 1423. The city's fortunes rebounded with the ambitious building projects of René of Anjou, Count of Provence, who strengthened the city's fortifications during the mid-15th century. During the 16th century the city hosted a naval fleet with the combined forces of the Franco-Ottoman alliance, which threatened the ports and navies of Genoa and the Holy Roman Empire.

Marseille lost a significant portion of its population during the Great Plague of Marseille in 1720, but the population recovered by mid century. In 1792 the city became a focal point of the French Revolution and was the birthplace of France's national anthem, La Marseillaise. The Industrial Revolution and establishment of the French Empire during the 19th century allowed for further expansion of the city, although it was captured and heavily damaged by Nazi Germany during World War II. The city has since become a major center for immigrant communities from former French colonies, such as French Algeria.

Prehistory[edit]

Humans have inhabited Marseille and its environs for almost 30,000 years: palaeolithic cave paintings in the underwater Cosquer Cave near the calanque of Morgiou date back to between 27,000 and 19,000 BC; and recent excavations near the railway station have unearthed neolithic brick habitations from around 6000 BC.[2][3]

Antiquity[edit]

Massalia, whose name was probably adapted from an existing language related to Ligurian,[4] was the first Greek settlement in France.[5] It was established within modern Marseille around 600 BC by colonists coming from Phocaea (now Foça, in modern Turkey) on the Aegean coast of Asia Minor. The connection between Massalia and the Phoceans is mentioned in Thucydides's Peloponnesian War;[6] he notes that the Phocaean project was opposed by the Carthaginians, whose fleet was defeated.[7] The founding of Massalia has also been recorded as a legend. According to the legend, Protis (in Aristotle, Euxenes), a native of Phocae, while exploring for a new trading outpost or emporion to make his fortune, discovered the Mediterranean cove of the Lacydon, fed by a freshwater stream and protected by two rocky promontories.[8] Protis was invited inland to a banquet held by the chief of the local Ligurian tribe, Nann, for suitors seeking the hand of his daughter Gyptis (in Aristotle, Petta) in marriage. At the end of the banquet, Gyptis presented the ceremonial cup of wine to Protis, indicating her unequivocal choice. Following their marriage, they moved to the hill just to the north of the Lacydon; and from this settlement grew Massalia.[8] Later, the natives would treacherously lay a plot to destroy the new colony, but the scheme was divulged and Conran, king of the natives, was killed in the ensuing battle.[9] Robb gives greater weight to the Gyptis story, though he notes that the tradition was to offer water, not wine, to signal the choice of a marriage partner.[10] A second wave of colonists arrived in about 540, when Phocaea was destroyed by the Persians.[11]

Massalia became one of the major trading ports of the ancient world. At its height, in the 4th century BC, it had a population of about 50,000 inhabitants on about fifty hectares surrounded by a wall. It was governed as an aristocratic republic, with an assembly formed by the 600 wealthiest citizens. It had a large temple of the cult of Apollo of Delphi on a hilltop overlooking the port and a temple of the cult of Artemis of Ephesus at the other end of the city. The drachmas minted in Massalia were found in all parts of Ligurian-Celtic Gaul. Traders from Massalia ventured into France on the rivers Durance and Rhône and established overland trade routes to Switzerland and Burgundy, reaching as far north as the Baltic Sea. They exported their own products: local wine, salted pork and fish, aromatic and medicinal plants, coral, and cork.[11] The most famous citizen of Massalia was the mathematician, astronomer and navigator Pytheas. Pytheas made mathematical instruments, which allowed him to establish almost exactly the latitude of Marseille, and he was the first scientist to observe that the tides were connected with the phases of the moon. Between 330 and 320 BC, he organized an expedition by ship into the Atlantic and as far north as England, and to visit Iceland, Shetland, and Norway, where he was the first scientist to describe drift ice and the midnight sun. Though he hoped to establish a sea trading route for tin from Cornwall, his trip was not a commercial success, and it was not repeated. The Massiliots found it cheaper and simpler to trade with Northern Europe over land routes.[12]

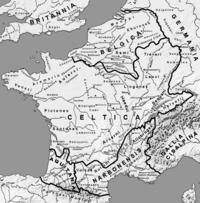

The city thrived by acting as a link between inland Gaul, hungry for Roman goods and wine (which Massalia was steadily exporting by 500 BC),[13][14] and Rome's insatiable need for new products and slaves. During the Punic Wars, Hannibal crossed the Alps north of the city. In 123 BC, Massalia was faced by an invasion of the Allobroges and Arverni under Bituitus; it entered into an alliance with Rome, receiving protection—Roman legions under Q. Fabius Maximus and Gn. Domitius Ahenobarbus defeated the Gauls at Vindalium in 121 BC—in exchange for yielding a strip of land through its territory which was used to construct the Via Domitia, a road to Spain. The city thus maintained its independence a little longer, although the Romans organized their province of Transalpine Gaul around it and constructed a colony at Narbo Martius (Narbonne) in 118 BC which subsequently competed economically with Massalia.

During Julius Caesar's war against Pompey and most of the Senate, Massalia allied itself with the exiled government; closing its gates to Caesar on his way to Spain in April of 49 BC, the city was besieged. Despite reinforcement by L. Domitius Ahenobarbus, Massalia's fleet was defeated and the city fell by September. It maintained nominal autonomy but lost its trading empire and was largely brought under Roman dominion. The statesman Titus Annius Milo, then living in exile in Marseille, joked that no one could miss Rome as long as they could eat the delicious red mullet of Marseille. Marseille adapted well to its new status under Rome. Most of the archaeological remnants of the original Greek settlement were replaced by later Roman additions. During the Roman era, the city was controlled by a directory of 15 selected "first" among 600 senators. Three of them had the pre-eminence and the essence of the executive power. The city's laws among other things forbade the drinking of wine by women and allowed, by a vote of the senators, assistance to a person to commit suicide.[citation needed]

It was during this time that Christianity first appeared in Marseille, as evidenced by catacombs above the harbour and records of Roman martyrs.[15] According to Provençal tradition, Mary Magdalen evangelised Marseille with her brother Lazarus. The diocese of Marseille became the Archdiocese of Marseille in 1948.

Middle Ages and Renaissance[edit]

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

The city was not affected by the decline of the Roman Empire before the 8th century, as Marseille enjoyed continued prosperity, probably thanks to its efficient defensive walls inherited from the Phoceans. Even after the town fell into the hands of the Visigoths in the 5th century, the city became an important Christian intellectual center with people such as John Cassian, Salvian and Sidonius Apollinaris. Marseille went on to a golden age in the 6th century as a major commercial center in the Mediterranean. Late Antiquity continued in the city until the 7th century, with Phocean and Roman infrastructure still in use (forums, baths). Marseille was occupied by Umayyad Arab forces in or before 736 at the invitation of the local ruler, duke Maurontus, as allies against his enemy Charles Martel. Marseille's prosperity ended suddenly in 739 when Martel's armies punished the city for rejecting Martel's appointed governor. The city did not develop again before the 10th century, as it suffered through 150 years of attacks by Greeks and Saracens.[citation needed]

The city regained much of its wealth and trading power in the 10th century under the counts of Provence.[citation needed] Between 1212 and 1218, the city was de facto governed by the Confraternity of the Holy Spirit.[16][17]

The Counts of Provence allowed Marseille, governed by a consul, great autonomy until the rule of Raymond Berengar IV of Provence. Marseille initially resisted his assertion of control, but acknowledged his suzerainty in 1243.[18] After his death, his daughter Beatrice of Provence married Louis IX of France's brother Charles I of Anjou in 1246, making him Count. Charles continued his father-in-law's administrative changes, which reignited discontent. Marseille rebelled in 1248, under the leadership of two local nobles, Barral of Baux and Boniface of Castellane, while Charles was embarked on the Seventh Crusade. Charles returned in 1250 and forced Marseille to surrender in 1252. Marseille rose up once more, in 1262, under Boniface of Castellane and Hugues des Baux, cousin of Barral des Baux (who remained loyal and helped contain the unrest).[19] Charles quelled the revolt in 1263. Trade prospered, and Marseille gave him no further trouble.[20] In 1348, the city suffered terribly from the bubonic plague, which continued to strike intermittently until 1361. As a major port, it is believed that Marseille was one of the first places in France to encounter the epidemic, and some 15,000 people died in a city that had a population of 25,000 during its period of economic prosperity in the previous century.[21] The city's fortunes declined still further when it was sacked and pillaged by the Aragonese in 1423.

Marseille's population and trading status soon recovered and in 1437, the Count of Provence René of Anjou, who succeeded his father Louis II of Anjou as King of Sicily and Duke of Anjou, arrived in Marseille and established it as France's most fortified settlement outside of Paris.[23] He helped raise the status of the town to a city and allowed certain privileges to be granted to it. Marseille was then used by the Duke of Anjou as a strategic maritime base to reconquer his kingdom of Sicily. King René, who wished to equip the entrance of the port with a solid defense, decided to build on the ruins of the old Maubert tower and to establish a series of ramparts guarding the harbour. Jean Pardo, engineer, conceived the plans and Jehan Robert, mason of Tarascon, carried out the work. The construction of the new city defenses took place between 1447 and 1453.[24][page needed] Trading in Marseille also flourished as the Guild began to establish a position of power within the merchants of the city. Notably, René also founded the Corporation of Fisherman.

Marseille was united with Provence in 1481 and then incorporated into France the following year, but soon acquired a reputation for rebelling against the central government.[25] Some 30 years after its incorporation, Francis I visited Marseille, drawn by his curiosity to see a rhinoceros that King Manuel I of Portugal was sending to Pope Leo X, but which had been landed on the Île d'If. As a result of this visit, the fortress of Château d'If was constructed; this did little to prevent Marseille being placed under siege by the army of the Holy Roman Empire a few years later.[26][page needed] Marseille became a naval base for the Franco-Ottoman alliance in 1536, as a Franco-Turkish fleet was stationed in the harbour, threatening the Holy Roman Empire and especially Genoa.[27] Towards the end of the 16th century, Marseille suffered yet another outbreak of the plague; the hospital of the Hôtel-Dieu was founded soon afterwards. A century later more troubles were in store: King Louis XIV himself had to descend upon Marseille, at the head of his army, in order to quash a local uprising against the governor.[28][page needed] As a consequence, the two forts of Saint-Jean and Saint-Nicholas were erected above the harbour and a large fleet and arsenal were established in the harbour itself.

18th and 19th centuries[edit]

Over the course of the 18th century, the port's defences were improved[29] and Marseille became more important as France's leading military port in the Mediterranean. In 1720, the last Great Plague of Marseille, a form of the Black Death, killed 100,000 people in the city and the surrounding provinces.[30] Jean-Baptiste Grosson, royal notary, wrote from 1770 to 1791 the historical Almanac of Marseille, published as Recueil des antiquités et des monuments marseillais qui peuvent intéresser l'histoire et les arts ("Collection of antiquities and Marseille monuments which can interest history and the arts"), which for a long time was the primary resource on the history of the monuments of the city.

The local population enthusiastically embraced the French Revolution and sent 500 volunteers to Paris in 1792 to defend the revolutionary government; their rallying call to revolution, sung on their march from Marseille to Paris, became known as La Marseillaise, now the national anthem of France. In 1793, the Federalists rise against the Jacobins. The rebellion becomes a monarchist fight against the republic. After the latter's victory, the city is renamed Ville-sans-nom ("Nameless-City") in punishment. In 14 July 1795, La Marseillaise becomes the official anthem and the city recovers its name.[31]

During the 19th century, the city was the site of industrial innovations and growth in manufacturing. The rise of the French Empire and the conquests of France from 1830 onward (notably Algeria) stimulated the maritime trade and raised the prosperity of the city. Maritime opportunities also increased with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.[32] This period in Marseille's history is reflected in many of its monuments, such as the Napoleonic obelisk at Mazargues and the royal triumphal arch on the Place Jules Guesde.

Coinciding with, and in support of, the Paris Commune of 1871, the populace established a commune of their own with the aid of local sections of the National Guard. The Commune was quickly suppressed by the army.[33]

1900 up to World War II[edit]

During the first half of the 20th century, Marseille celebrated its "port of the empire" status through the colonial exhibitions of 1906 and 1922;[34] the monumental staircase of the railway station, glorifying French colonial conquests, dates from then. In 1934, Alexander I of Yugoslavia arrived at the port to meet with the French foreign minister Louis Barthou. He was assassinated there by Vlado Chernozemski.

In the interwar period, Marseille was known for its extensive organised crime networks. Simon Kitson has shown how this corruption extended into local administrations like the Police.[35]

During the Second World War, Marseille was bombed by German and Italian forces in 1940. The city was occupied by the Germans from November 1942 to August 1944. On 22 January 1943, over 4,000 Jews were seized in Marseille as part of "Action Tiger". They were held in detention camps before being deported to Poland occupied by Nazi Germany to be murdered.[36] The Old Port was destroyed in January 1943 by the Germans. The city was liberated by the Allies on 29 August 1944. As a part of Operation Dragoon, General Joseph de Goislard de Monsabert led roughly 130,000 French troops to liberate the city. Similar to the liberation of other major French cities (such as Paris and Strasbourg), the local German garrison was defeated by mainly French forces, with limited American support.[citation needed]

Marseille after World War II[edit]

After the war, much of the city was rebuilt during the 1950s. The governments of East Germany, West Germany and Italy paid massive reparations, plus compound interest, to compensate civilians killed, injured, left homeless or destitute as a result of the war.

From the 1950s onward, the city served as an entrance port for over a million immigrants to France. In 1962, there was a large influx from the newly independent Algeria, including around 150,000 returned Algerian settlers (pieds-noirs).[37] Many immigrants have stayed and given the city a French-African quarter with a large market.

In December 1994, the Marseille Provence Airport was where the GIGN stormed Air France Flight 8969, which had been hijacked by 4 GIA terrorists. All four hijackers were killed and the passengers were freed.

In the 21st century Marseille regularly attracts media attention due to drug trafficking and shootings that take place especially in the north of the city.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Patrick Boucheron, et al., eds. France in the World: A New Global History (2019) pp 30-35.

- ^ J. Buisson-Catil, I. Sénépart, Marseille avant Marseille. La fréquentation préhistorique du site. Archéologia, no. 435, July–August 2006, pages 28–31

- ^ "Marseille before Massalia, the oldest Neolithic unfired brick architecture in France" (Press release). Inrap (Institut national de recherches archéologiques preventives). 15 February 2007. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Peregrine, Anthony (14 October 2015). "Marseille city break guide". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, p. 42.

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 1.13.6

- ^ a b Duboi, Marius; Gaffarel, Paul; Samat, J.-B. (1913). Histoire de Marseille (in French). Marseille: Librairie P. Ruat.

- ^ M. Guizot, History of France, Vol. I., chap. I., Gaul (Kindle Edition)

- ^ Robb, Graham, The Discovery of Middle Earth, p. 6

- ^ a b Palanque 1990, p. 41.

- ^ Palanque 1990, p. 44.

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, pp. 49–54, "Du commerce à l'exploration". Evidence of trade is provided by the circulation of silver drachmas minted in Marseille from 525 BC, as well as exported pottery from 550 BC; wine produced in Marseille was distributed throughout Gaul during this period.

- ^ Johnson, Hugh (1989). Vintage: The Story of Wine. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-671-68702-1.

By 500BC Massalia was making its own wine, and its own amphoras to export it.

- ^ Goyau, Pierre-Louis-Théophile-Georges (1913). "Diocese of Marseilles (Massalia)". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. The martyrdom of St. Victor took place under the Roman Emperor Maximian.

- ^ Damien Carraz, "Precursors and Imitators of the Military Orders: Religious Societies for Defending the Faith in the Medieval West (11th–13th c.)," Viator 41.2 (2010): 91–111, at 106.

- ^ Damian J. Smith, Crusade, Heresy and Inquisition in the Lands of the Crown of Aragon (c. 1167–1276) (Brill, 2010), pp. 42–47.

- ^ Abulafia 1999, p. 373: "[Some, like] Marseilles, had had their consulates confirmed by the counts and were close to enjoying complete independence. Ramon-Berenguer V set out to reverse this ... Marseille, however, refused ... the Marseillais did recognize Ramon-Berenguer's suzerainty in 1243."

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1958). The Sicilian Vespers: A History of the Mediterranean World in the Later Thirteenth Century. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–76. OCLC 315065012.

- ^ Abulafia 1999, p. 374: "[Marseille] was subdued once and for all in 1263. Probably the major factor in reconciling the Provençal towns to the loss of their independence was their general economic prosperity."

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, p. 182.

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, pp. 160–161, 174This commandry was a monastery belonging to the military religious order of the crusading Knights Hospitaller. Following Richard the Lionheart's visit in 1190 with the Anglo-Norman fleet during the Third Crusade, Marseille became a regular port of call for crusaders.

- ^ Busquet, Raoul; Laffont, Robert (1998). Histoire de Marseille. Jeanne Laffitte. ISBN 2-221-08734-8. (in French)

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, page needed B.

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998Chronology, page 182, and Part III, Chapters 25–36.

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, page needed C.

- ^ Leathes, Stanley (1906). Ward, Adolphus William; Prothero, G.W.; Leathes, Stanley (eds.). The Cambridge Modern History. Vol. 10. Cambridge: University Press. p. 72. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, page needed D.

- ^ 1720 chart of Marseille: a contemporary chart showing the defenses of the port.

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, p. 360–378.

- ^ Prin-Derre, Jérémy (2 August 2015). "Marseille, la ville rebelle, devient la Ville-sans-nom". www.laprovence.com (in French). Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ Ghiuzeli, Haim F. "The Jewish Community of Marseilles". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ Milza, Pierre, La Commune, September 10th 2009, pp. 165–170

- ^ Landau, Paul Stuart; Kaspin, Deborah D. (2002), Images and empires: visuality in colonial and postcolonial Africa, University of California Press, p. 248, ISBN 0-520-22949-5

- ^ Kitson 2014.

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (1986). The Holocaust: The Jewish Tragedy. Collins. pp. 530–531.

- ^ Moore, Damian. "Multicultural Policies and Modes of Citizenship in European Cities: Marseilles" (DOC). UNESCO. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

Works cited[edit]

- Abulafia, David, ed. (1999). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36289-X.

- Duchêne, Roger; Contrucci, Jean (1998). Marseille, 2600 ans d'histoire [Marseille, 2600 Years of History] (in French). Paris: Editions Fayard. ISBN 2-213-60197-6.

- Kitson, Simon (2014). Police and Politics in Marseille, 1936–1945. Amsterdam: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24835-9.

- Palanque, J.R. (1990). "Ligures, Celtes et Grecs" [Ligures, Celts and Greeks]. In Baratier, Edouard (ed.). Histoire de la Provence [History of Provence]. Univers de la France (in French). Toulouse: Editions Privat. ISBN 2-7089-1649-1.