Boulton and Park

Thomas Ernest Boulton and Frederick William Park were Victorian cross-dressers. Both were homosexual men from upper-middle-class families, both enjoyed wearing women's clothes and both enjoyed taking part in theatrical performances—playing the women's roles when they did so. It is possible that they asked for money for sex, although there is some dispute over this. In the late 1860s they were joined on a theatrical tour by Lord Arthur Clinton, the Liberal Party Member of Parliament for Newark. Also homosexual, he and Boulton entered into a relationship; Boulton called himself Clinton's wife, and had cards printed showing his name as Lady Arthur Clinton.

Boulton and Park were indiscreet when they cross-dressed in public, and came to the attention of the police. They were under police surveillance for a year before they were arrested in 1870, while in drag, after leaving a London theatre. When they appeared at Bow Street Magistrates' Court the morning after the arrest they were still clothed in the women's dresses from the previous evening; a crowd of several hundred people were there to see them. The two men were subjected to an intrusive physical examination from a police surgeon and held on remand for two months. They were charged with conspiracy to commit sodomy, a crime that carried a maximum prison sentence of life with hard labour. Just before the case started Clinton died, possibly of scarlet fever or suicide; it is also possible his death was faked and he fled abroad. The case came before the Court of the Queen's Bench the following year, Boulton and Park with three other men. All five were found not guilty after the prosecution failed to establish that they had anal sex. The judge, Sir Alexander Cockburn, the Lord Chief Justice, was highly critical of the police investigation and the treatment of the men by the police surgeon. Boulton and Park admitted to appearing in public dressed as women, which was "an offence against public morals and common decency".[1] They were bound over for two years.

The case was reported in all the major newspapers, often in lurid terms. Several penny pamphlets were published focusing on the sensational aspect of the case. The events surrounding Boulton and Park are seen as key moments in the gay history of the UK. The arrest and trial have been interpreted differently over time, from innocent Victorian sentimentalism to a wilful ignoring of the men's sexuality by the courts to ensure they were not convicted. Recent examinations have been from the perspective of transgender history. The case was a factor that led to the introduction of the 1885 Labouchere Amendment which made male homosexual acts punishable by up to two years' hard labour. Boulton and Park both continued performing on stage after the trial, and both worked for a while in the US. Park died in 1881, probably of syphilis; Boulton died in 1904 from a brain tumour.

Background[edit]

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, male homosexual acts were illegal under English law and were punishable by imprisonment under section 61 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861. The Act abolished the death penalty for sodomy which had been part of Henry VIII's Buggery Act 1533.[2] Under the 1861 act, sodomy in the UK carried a life sentence in prison with hard labour.[3] Cases involving homosexual activity were rarely brought to trial, however, and those that were had a lower conviction rate than other crimes—there was a 28 per cent conviction rate for sodomy against a 77 per cent rate for all other offences. The sociologist Ari Adut observes that most suspects were either caught having sex in public, or were targets of a politically motivated prosecution.[4] Many suspects were allowed to leave the country before trial.[2]

The concept of homosexuality was known to but not understood by the authorities in the 1870s. The historian and sociologist Jeffrey Weeks considers that the idea of homosexuality was "extremely undeveloped both in the Metropolitan Police and in high medical and legal circles, suggesting the absence of any clear notion of a homosexual category or of any social awareness of what a homosexual identity might consist".[5] Such ignorance by the medical profession was seen as proof that homosexual activity was not undertaken in Britain, in contrast to the knowledge gained by French and German doctors.[6] For British medico-jurisprudent works, such as Alfred Swaine Taylor's 1846 work A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence, the act of sodomy was linked to bestiality, and described as "the unnatural connection of a man with a man or with an animal. The evidence required to establish it is the same as in rape, and therefore penetration alone is sufficient to constitute it".[7]

While the authorities were ignorant of the extent of homosexuality in Britain, some parts of the West End of London—including the Burlington Arcade, just off Piccadilly—were associated with homosexuality and male prostitution. According to the historian Matt Cook, this "confirm[ed] the association of homosexual behaviour with fashion, effeminacy and monetary transaction".[8] This burgeoning homosexual culture was aligned with effeminacy and cross-dressing, according to the literary scholar Joseph Bristow, in his work "Remapping the Sites of Modern Gay History".[9] Public opinion—and the opinion of the authorities—was never against those men caught up in homosexual scandals, according to Adut. As examples he cites those associated with the 1889 Cleveland Street scandal, who remained in positions in society, except one, who left the country; similarly, when Boulton and Park were cleared of the main charges against them, they continued acting in Britain and abroad.[10]

Cross-dressing was not illegal in the 1870s; it was associated with the theatre, particularly pantomime; there was no association in the minds of the general public between cross-dressing and homosexuality.[11] When arrests were made for cross-dressing, it was under the charge of occasioning a breach of the peace.[12] There had been cases of cross-dressing heard in the courts in the second half of the 19th century: in 1858 two men, one 60 years old and one 35, were arrested at an unlicensed dancing room. The 60-year-old was dressed as a Dresden shepherdess, the 35-year-old in modern female dress; they were arrested on grounds they had acted "for the purpose of exciting others to commit an unnatural offence".[13] The same year a landlady reported her lodger for behaving indecently in the parlour window while dressed in women's clothing.[14]

Early lives[edit]

Thomas Ernest Boulton[edit]

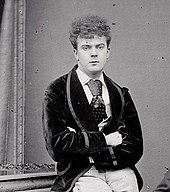

Thomas Ernest Boulton—commonly known as Ernest—was born on 18 December 1847 at Kings Road, Tottenham, Middlesex (now London); he was the older of two boys who survived past infancy. His parents were Thomas Alfred Boulton, a wine merchant, and his wife, Mary Ann (née Levick).[15] The Boultons had three other sons who died of tuberculosis in infancy; Ernest was a sickly baby who his parents thought also had the condition. During childhood he also developed a fistula in his rectum which needed surgery.[15][16][a]

Neil McKenna, who wrote a biography of Boulton and Park, described Boulton as "pretty with his blue-violet eyes, large as saucers in his pale face, and his dark hair cascading in baby curls";[18] McKenna notes that as a child, Boulton was often mistaken for a baby girl.[18] From the time he was six Boulton began dressing up and acting as a girl, often as a parlourmaid. He once dressed up and served his unknowing grandmother at the dinner table. When he left the room, she commented to Boulton's mother "I wonder, having sons, that you have so flippant a girl about you".[15]

As Boulton grew up he continued cross-dressing, a practice about which his parents were indulgent.[15] When he was about eighteen his father discussed a potential career in the professions, but Boulton said he wanted to work in the theatre. His father got his way, and in 1866 Boulton began work as a clerk at the Islington branch of the London and County Bank. He did not like the work, and his attendance was often sporadic; he resigned from the position soon after his employers had written to Boulton's father to question whether his son was suitable for the bank.[19] Boulton was homosexual[20] and was known to his friends as Stella,[15] although sometimes also by Miss Ernestine Edwards.[21] In 1867 he was arrested with his friend Martin Cumming in the Haymarket—a known venue for prostitution—when they were wearing dresses and soliciting men for sex; no charges were brought. He was arrested again a few weeks later for the same offence, this time with a man called Campbell, a transvestite male prostitute who went under the sobriquet Lady Jane Grey. The two appeared at Marlborough Street Magistrates Court where they were fined.[22]

Frederick William Park[edit]

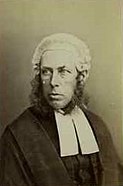

Frederick William Park was the third son and twelfth child of Alexander Atherton Park, the Master of the Court of Common Pleas—one of the superior courts of Westminster—and his wife, Mary.[23] He was baptised on 5 January 1847 at St Mary's Church, Wimbledon.[24] Park's mother died before his third birthday. He grew up in the family home at Wimpole Street, central London, where he was educated at home by his sisters and a governess.[25]

Park's eldest brother, Atherton, was killed while serving with the 24th Bombay Native Infantry in Jhansi, India, while Park was still young.[26] His other brother, Harry, was arrested at about the age of 16—when Park was 11 or 12—for homosexual activity. Harry's Italian boyfriend had attempted to blackmail him over their affair, and when Harry refused to pay, reported him to the police. He vehemently denied the accusations at a magistrates' court and the case was dismissed. Harry was open with his younger brother about his homosexuality and, McKenna suggests, had probably guessed that Park was also gay. Harry called his brother "Fan" or "Fanny" from a young age. On 1 April 1862, two or three years after the court appearance, Harry was arrested for indecent assault on a police officer in Weymouth Mews (off Weymouth Street). In court again, bail of £600 was set.[27][b] Harry was sentenced to a year's hard labour, and was then sent to Scotland by his father to avoid further scandal.[29][30] Park's father decided the best profession for Frederick was within the law, and arranged for him to be articled with a solicitor in Chelmsford, Essex.[31]

Park was a regular cross-dresser and went under several names when in women's attire, including Fanny Winifred Park,[32] Mrs Mable [sic] Foster, Mrs Jane,[33] Mabel Foley[21] and Fanny Graham.[34]

Fanny and Stella[edit]

There is no record of when Boulton and Park first met, but the two became close friends, with a joint love of the stage and of cross-dressing. They would go out in public dressed in either—and sometimes both—male and female attire. According to McKenna it is probable that they both acted as male prostitutes at times,[36] although Richard Davenport-Hines, writing for the Dictionary of National Biography says "they were not prostitutes but sometimes asked their admirers for money".[15]

When the two appeared in public wearing female attire many of those who saw them believed they were women.[37] In drag, they watched the 1869 Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, went shopping in London's West End, ate at restaurants and went to the theatre and music halls.[15][38][39] According to the theatre historian Laurence Senelick, Boulton and Park's "simpering and mincing that had ... [them] thrown out of the Alhambra Music Hall when in women's clothes, and out of the Burlington Arcade when in men's clothes" were popular when they were engaged in their theatricals.[37] When they went out in male attire, Boulton and Park would wear tight trousers and shirts open at the collar, wearing make-up; this was, according to Senelick, "more disturbing and offensive to passers-by than their drag".[40] To store their dresses, cosmetics and other items, as well as a base from which they went out, the two rented a small flat at 13 Wakefield Street, off Regent Square.[15]

In the late 1860s Boulton and Park were part of a theatre troupe that toured Britain, giving private theatricals. In addition to private houses, they appeared on stage in the Egyptian Hall, Chelmsford; Brentwood and Southend, Essex; and the Spa Rooms at Scarborough, North Yorkshire.[35] They always took the female roles and dressed accordingly; in the theatre programmes, their names were listed as Boulton and Park, and audience members knew the parts were played by two men.[41][42][43][c] In 1868 they were joined on tour by Lord Arthur Clinton, the Liberal Party Member of Parliament for Newark, who performed in male roles in the entertainment. They played husband and wife on the stage, and shared an on-stage kiss; it raised no complaints from any of the audiences or in the local press.[46]

Clinton had been in a relationship with Boulton for about a year; although there is no evidence that their relationship was sexual, it is considered very likely, according to several historians, including Charles Upchurch,[46] Sean Brady[47] and McKenna.[48] Boulton called himself Clinton's wife, and had cards printed showing his name as Lady Arthur Clinton.[49]

Boulton and Park had been so flagrant in their behaviour that they came to the attention of the police, and the pair had been under surveillance for over a year prior to their arrest.[50][51]

Arrest and investigation[edit]

On the evening of 28 April 1870 Boulton and Park—both in drag—went to the Strand Theatre where they had reserved a box; they were accompanied by two friends, Hugh Mundell and Cecil Thomas, both of whom were wearing male attire. When the group left the theatre and ordered a cab, Boulton and Park were arrested; Thomas ran off and Mundell accompanied the pair to the police station in Bow Street.[52][53] As the police were unsure whether Boulton and Park were male or female—despite both stating they were men dressed as women for a "lark"—they were ordered to undress, and did so, in front of several policemen. The two men were kept in Bow Street overnight and were kept company by Mundell, who had been arrested at the station for refusing to give his name and address.[54]

The following morning Boulton and Park were taken across the road into Bow Street Magistrates' Court; they were still wearing their dresses from the previous evening. A crowd of several hundred people had gathered to see the two make their way into court. McKenna observes that their arrest was too late to appear in the morning papers, and it is not known how the news had travelled so widely in such a short space of time. The court room was also full of spectators.[55] The two men were charged that they:

did with each and one another feloniously commit the abominable crime of buggery,

further that they did unlawfully conspire together, and with divers other persons, feloniously, to commit the said crimes further that they did unlawfully conspire together, and with divers other persons to induce and incite other persons feloniously with them to commit the said crime

and further that they being men, did unlawfully conspire together, and with divers others, to disguise themselves as women and to frequent places of public resort, so disguised, and to thereby openly and scandalously outrage public decency and corrupt public morals.[56]

The court heard from four policemen, one of whom had visited the Wakefield Street flat that morning and showed the magistrate a series of photographs of Boulton and Park in male and female attire. He told the court he had conducted surveillance on Boulton and Park for the previous year. Another policeman stated he had been on surveillance duty at the Wakefield Street flat for the past fortnight, and had seen the late-night comings and goings of the two men. The magistrate remanded Boulton and Park in custody for seven days;[57] they were held at the Coldbath Fields Prison.[58]

They left the court and returned to the neighbouring police cells where they were physically examined without consent by James Paul, the doctor who worked with the Bow Street division of the Metropolitan Police.[59] Paul inspected the anuses of both men. On Boulton he reported "The anus was dilated, and more dilatable, and the muscles surrounding the anus easily opened"; on Park he said "The anus was very much dilated, ... and dilatable to a very great extent. The rectum was large, and there was some discoloration around the edge of the anus, caused probably by sores".[60] Although not an expert in sexual activity, he deemed "there were symptoms in these men as I should expect to find in men that had committed unnatural crimes".[61][62] He also noted that both Boulton and Park had large penises and Boulton also had a scrotum "of inordinate length"; he said this was a result of their sodomy.[63][d] To counter the evidence, the defence arranged for six doctors, including Frederick Le Gros Clark—the examiner from the University of London—and the doctor of Coldbath Fields—to physically examine Boulton and Park. They all concluded that there was no evidence of sodomitical activity and that there was nothing abnormal in the size of either man's penis. The only point that was out of the ordinary was Boulton's operation scar from the removal of the fistula.[65][66]

When Boulton and Park appeared at the Bow Street court for re-examination the following week, a crowd of around a thousand was gathered outside the court to see them arrive, and the courtroom was full to capacity.[67] Some of the crowd were disappointed to see them dressed in male attire.[68] When examined, Mundell stated that he "believed Boulton to be a woman", and made amorous advances to her accordingly.[69] A list of items seized from the Wakefield Street flat was read out: it included numerous items of women's clothing, ladies shoes and boots, wigs, hair pieces, hairdressing equipment, make-up and wadding—the last of which was used for padding.[70] Bail was refused, and Boulton and Park were again put on remand; they were told that there would be more attendances at the court for examination.[68]

Boulton and Park appeared for examination at the magistrates' court seven times by 28 May,[65][e] and details of the evidence gathered by the police was included in the hearings.[69][76] The police investigation, under the control of Superintendent James Thompson, continued while Boulton and Park were on remand and their findings were raised in the magistrates' court. Witnesses who came forward to the police included John Reeve—a manager at the Alhambra Theatre of Variety—and George Smith, the beadle of Burlington Arcade; both men reported that they had ejected Boulton and Park from their respective premises on numerous occasions.[77] Thompson travelled to Edinburgh and interviewed the landlady of Louis Hurt, a Post Office surveyor and friend with whom Boulton had stayed. Thompson tried to get the landlady to agree with the premise that Boulton and Hurt regularly shared a bed together; she told the detective that Boulton slept in a different room. Thompson removed photographs of Boulton and correspondence between the two men. Following the trail of correspondence, police also interviewed John Safford Fiske, the American consul in Leith, and again removed photographs and correspondence.[78]

Boulton and Park were released from remand on 11 July 1870, having been held for over two months.[79] The police investigation continued and, in addition to Boulton and Park, charges were brought against Clinton, Hurt, Fiske and three others who were found to be connected: William Somerville, Martin Cumming and C. F. Thomas.[80] Somerville had accompanied Boulton and Park to a ball; they had been in drag, he had been in male clothing. He had also written letters to Boulton which the police had found; they were the basis of the charge against him.[81] Thomas was an independently wealthy man who was driven to meet the others in his own carriage. He and Cumming would both join the others in public in women's clothing.[82] Somerville, Cumming and Thomas all absconded before the trial.[83][84] Charges against Mundell were dropped, and he was listed as a witness for the prosecution.[85]

On 18 June 1870 it was reported that Clinton had died of scarlet fever. He made a deathbed denial against the accusations of sodomy and dictated a note to his solicitor: "Nothing can be laid to my charge other than the foolish continuation of the impersonation of theatrical characters which arose from a simple frolic in which I permitted myself to become an actor."[86] He was buried on 23 June in Christchurch, Hampshire.[87] Given the circumstances Clinton was in, it is possible that he killed himself,[88] although McKenna considers it likely that there was no suicide, but that he lived abroad, possibly in Paris, Sydney or New York.[89]

Initially it was thought that the case against the men would be heard in the Old Bailey, but on 4 July Boulton's counsel applied for the case to be moved to the Court of the Queen's Bench to be heard before Sir Alexander Cockburn, the Lord Chief Justice. The legal historian Judith Rowbotham considers this was "the first hint that the prosecution was falling apart".[90][f] Davenport-Hines considers that failure was because the police "failed to cajole the parties to denounce each other or to muster convincing witnesses".[15]

Trial[edit]

The trial ran between 9 and 15 May 1871 before a special jury.[80][92][g] The prosecution was led by Sir Robert Collier and Sir John Coleridge, the Attorney General and Solicitor General, respectively, and the team included Hardinge Giffard—who was later the Lord Chancellor—and Henry James, who later held the positions of both Attorney General and Solicitor General.[15] The defendants were represented by Sir George Lewis.[94] Both Boulton and Park dressed in male clothing for the trial and both had grown facial hair in the year since their arrest; Davenport-Hines considers this was probably at the direction of Lewis.[94]

With no physical evidence that sodomy had taken place and no witnesses to homosexual activity by any of the accused, the prosecution said that the lifestyles of the men—their public displays of transvestitism—were proof of homosexual activity.[95] The defence stated that Boulton's and Park's actions were not criminal but feckless and immature. Their theatrical background playing women's roles was used as a defence and to explain their possession of women's clothing.[96][1] Rowbotham notes that Clinton's deathbed confession would have had an impact on the jury; such statements were taken seriously and would have undermined the prosecution's case.[97]

The witnesses produced by the prosecution proved disastrous for them,[98] and many told the court they had seen no evidence of homosexual or improper behaviour.[1] Mundell told the court that Boulton and Park had told him several times—verbally and in correspondence—that they were men in drag, but he had disbelieved them. He recounted that Boulton had rebuffed physical advances, rather than encouraging any homosexual activity.[99] Smith, the beadle, commented extensively on his dismissal for accepting tips from female prostitutes to ply their trade in Burlington Arcade;[98] he told the court he had been "getting up evidence for the police in this little affair" and that he expected to be paid by the police for giving evidence.[100] The prosecution presented and read out in court examples of the correspondence involving the accused men, the defence argued that these were shows of affection between the writers—albeit with language exaggerated by "theatrical propensities"—and not evidence of a physical relationship.[101][102]

One of the defence witnesses was Boulton's mother, who told the court that she knew and approved of her son's friendship with Clinton. According to Rowbotham, Mary Boulton's testimony "gave the impression that while Boulton had been foolish in extending his wearing of female attire beyond ... [his theatrical] performances, it was also an indication of how they had all continued play-acting off-stage".[1] Boulton's parents had accompanied him and Clinton to the theatre—with Boulton in male attire—and both parents had seen him perform on stage. According to Morris Kaplan, in his history of homosexuality in the late nineteenth-century, Boulton's mother "portrayed the group of cross-dressers and their admirers as a cozy domestic circle of young male friends".[41]

Cockburn's summing up was critical of the prosecution's case and the behaviour of the police.[103] He said that the investigation in Scotland, and charges against Fiske and Hurt were excessive.[104] He also commented that the police had no jurisdiction to act without a warrant in Scotland and that the court had no jurisdiction to try people for an event that took place in Scotland, which was a matter for the Scottish courts, operating under Scots law.[92][105] He considered that Paul's physical examination was improper,[106] and he doubted that the police had made a sufficiently strong case that proved homosexual activity had taken place. There was no doubt, he said, that some of the accused had appeared in public in women's clothing, and suggested that such outrages of public decency should be addressed by future legislation that allowed sentences "of two or three months' imprisonment, with the treadmill attached to it, with, in case of repetition of the offence, a little wholesome corporal discipline, would, I think, be effective, not only in such cases, but in all cases of outrage against public decency."[107]

After deliberating for fifty-three minutes the jury found all four men not guilty.[108] At the announcement, Boulton fainted;[15] there was applause, cheers and cries of "Bravo!" from the public gallery.[109][110] Kaplan observes that the case "was fraught with contested issues touching on gender, sexuality, social class and urban culture".[111]

On 6 June 1871 the last remaining matter from the court case was brought to a close. Boulton and Park had a remaining charge of appearing in public dressed as women, which was "an offence against public morals and common decency". They met Cockburn in his chambers, where they dropped their pleas of not guilty to accept being bound over for two years against a sum of 500 guineas each.[1][112]

Post-trial lives[edit]

After the trial Boulton returned to performing and appeared in Eastbourne in September 1871;[113] that October he appeared on stage in Burslem and Hanley, Staffordshire, before performing in Bolton, Lancashire.[114][115][116] From 1874 he spent some time in New York, performing under the name Ernest Byrne,[117] and it is possible he met Clinton there.[89] Boulton returned to Britain in 1877 and again toured. He died on 30 September 1904 at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, from a brain tumour.[15]

Park also travelled to New York and appeared on stage under the name Fred Fenton, where he had some limited success in character parts and was a resident performer at the Fifth Avenue Theatre for a time. He died in 1881, aged 33[118] or 34, probably of syphilis, according to McKenna.[119]

Newspaper coverage[edit]

The arraignment hearings and trial were widely reported in national and local press in Britain, and most of the London papers had provided extensive space for the coverage.[120] Boulton's and Park's private lives—and those of their known friends and associates—were scrutinised and publicised in the press; they appeared under sensational headlines, including "Men in Petticoats", "The Gentlemen Personating Women", "The 'Gentlemen-Women' Case" and "The 'Men-Women' at Bow Street".[121]

Many of the papers included leaders that were indignant that homosexuality—which was considered a foreign habit—was being practised in England.[122] After the acquittal, some of the leader writers changed their stances, and The Times said they had "a certain sense of relief that we record this morning the failure of a prosecution"; a guilty verdict, the leader writer continued, "would have been felt at home, and received abroad, as a reflection of our national morals".[4][123]

In the reports after their first appearance at the magistrates' court, most major newspapers included extensive descriptions of Boulton's and Park's attire and hair style.[20][124] This included the quality press, including The Times, which reported:

When placed in the dock Boulton wore a cherry-coloured silk evening dress trimmed with white lace; his arms were bare and he had on bracelets. He wore a wig and painted chignon. Park's costume consisted of a dark green satin dress, low necked, trimmed with black lace, of which material he also had a shawl round his shoulders. His hair was flaxen and in curls. He had on a pair of white kid gloves.[53]

In addition to the extensive newspaper coverage, several penny pamphlets were produced with titles that included "Men in Petticoats", "The Unnatural History and Petticoat Mystery of Boulton and Park", "Stella, the Star of the Strand", "The Lives of Boulton and Park: Extraordinary Revelations", "Life and Examination of the Would-be Ladies" and "The Life and Examination of Boulton and Park, the Men in Women's Clothing".[125][126] Many showed illustrations of Boulton and Park in male and female attire.[127] Michelle Liu Carriger, in her examination of the penny pamphlets, identifies a change in the approach taken by the illustrators. In the early publications, Boulton and Park are portrayed as attractive ladies; by four weeks into the magistrate's hearing, they are shown as a "distinctly more grotesque masculine cast".[128] This was particularly true in the illustrations of The Illustrated Police News,[128] one of the more lurid publications of the time.[129][h] Kaplan observes that many of the penny pamphlets carried "ritual condemnation" of the accused men, not in keeping with the sensational nature of the images and details in the publications.[131]

Historiography[edit]

The historian Harry Cocks states that the interpretation of history of the Boulton and Park arrest and trial "has gone through distinct phases";[108] the professor of English Simon Joyce, considers that interpretations are consistent in their treatment of Boulton and Park as men.[132] Cocks identifies the following themes: the lawyer William Roughhead thought the relationship to be largely innocent and sprang from the sentimental romanticism that the Victorians adopted; the barrister H. Montgomery Hyde wrote that Boulton and Park were homosexuals who were not imprisoned because there was insufficient evidence presented in court. Weeks and Alan Sinfield, the gender studies academic, argue that the court ignored the possibility of homosexuality, which meant a conviction was not possible. Cocks considers that both Upchurch and Bartlett write that the courts demonstrated "wilful ignorance" that refuted the possibility that there was a homosexual element in society.[108] Senelick identifies and studies Boulton and Park in relation to stage drag artistes.[133][134]

Joyce sees the common theme that Boulton and Park were considered at the time, and in subsequent studies, as two men who dressed in women's clothing.[132] He views the story of Boulton and Park from the position of a transgender history. He observes that one of the major British newspapers—and some of the hearings in the magistrates' courts—use feminine pronouns in describing the accused, and of Mary Boulton's evidence that her son "has presented as female since the age of six".[135] Joyce argues that:

Fanny and Stella's story is studded with moments of recognition and also with aspects that are barely comprehensible today, and I want to argue that those points of apparent incommensurability with current thinking are just as valuable in helping us understand transgender people as having a history, albeit one that is sometimes fractured and non-linear.[136]

Legacy[edit]

Cocks describes the Boulton and Park trial as "one of the central parts of any history of male homosexuality";[39] Jason Boyd, in Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History, describes the trial as:

a significant moment in the history of the hesitant emergence of a public discourse of the homosexual as an identity. Perhaps more importantly, the base is significant in its revelation of a "pre-homosexual" subculture which was obviously extensive, varied and flourishing, involving, in differing roles and degrees, men of all walks of life.[137]

The Crown's failure to secure the prosecution of Boulton and Park showed the difficulties in investigating private activities, particularly offences for homosexual activity. The failure to convict the men was one factor in the introduction of the 1885 Labouchere Amendment.[138][132] This—formally, section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, named after its sponsor, Henry Labouchère—made male homosexual acts punishable by up to two years' hard labour.[139] According to the historian William A. Cohen, at the time of the Boulton and Park case, homosexuality was "identifiable within a sociomedical sexual taxonomy, but was not yet recognized as a juridical subject".[140] The subsequent introduction of the Labouchere Amendment, "virtually criminaliz[ed] gay male style itself".[140]

During the hearings in May 1870, Reynolds's Newspaper reported that a witness said "'We shall come in drag', which means wearing women's costumes"; the magistrate commented that "This is the first time the meaning of the word 'drag' has been given in evidence?"[141] The exchange is listed in the Oxford English Dictionary as the first known use of the term "drag" for cross-dressing.[142]

Portrayals[edit]

Boulton and Park appear as characters in The Sins of the Cities of the Plain, an 1881 work of homosexual pornographic literature by John Saul, a male prostitute.[143] In the work, Boulton was named "Laura" and Park was named "Selina".[127] In the story, the cross-dressing narrator recounts how he meets Boulton and Park, dressed as women, at Haxell's Hotel on the Strand, with Clinton. Later on, the narrator spends the night at Boulton and Park's rooms in Eaton Square, and the next day has breakfast with them "all dressed as ladies".[144] According to Cohen, the work "provides a piquant complement to the other narratives of their lives, valuable both for radically shifting the perspective and for highlighting the tendentiousness of any report about 'sodomitical practices'."[145]

Boulton and Park appear in the plays Lord Arthur's Bed (2008) by the playwright Martin Lewton,[146] Fanny and Stella: The Shocking True Story (2015) by Glenn Chandler[147] and Stella, by Neil Bartlett; the last of these was co-commissioned by the London International Festival of Theatre, Holland Festival and Brighton Festival in 2016.[148][149] Boulton and Park are also the subjects of a Victorian limerick that was popular at the time of the case.[145] Cohen considers it shows an "anachronistic conflation of sodomy and bestiality".[145] The historian Angus McLaren judges that the limerick shows that at the time there was a "popular belief that homosexuality and transvestism were inseparable".[150] According to the historian Catharine Arnold, the limerick showed that the Boulton and Park case "lived on in popular culture".[151]

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The fistula was removed by surgery in February 1869.[17]

- ^ £600 in 1862 equates to approximately equivalent to £60,000 in 2021, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[28]

- ^ The works performed included the comedy A Morning Call—in which Boulton appeared as Mrs Chillington[44]—and a charity performance of singing the ballads "Fading Away" and "My Pretty Jane".[45]

- ^ When asked in court how sodomy could have enlarged their penises and testicles, he said that it was because of the "traction" involved in anal sex.[64]

- ^ Boulton and Park appeared before the magistrates' court on 6,[68] 13,[71] 15,[72] 20–22,[73][74] 28[65] and 31 May 1870.[75]

- ^ The Queen's Bench was the most senior English court of common law. The Boulton and Park case was the only trial for sodomy that came up before the Queen's Bench that century.[91]

- ^ Special juries comprised people of a defendant's own social status, and were made up of "every person who comes up to a certain qualification as banker, or esquire, or of a higher degree".[93]

- ^ In 1886 The Illustrated Police News was voted the worst newspaper in England by readers of Reynolds's Newspaper.[130]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Rowbotham 2015, p. 143.

- ^ a b Spencer 1995, p. 275.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 36.

- ^ a b Adut 2005, p. 226.

- ^ Weeks 1989, p. 101.

- ^ Crozier 2005, p. 129.

- ^ Taylor 1846, pp. 560–561.

- ^ a b Cook 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Bristow 2007, p. 132.

- ^ Adut 2005, p. 239.

- ^ Brady 2009, p. 71.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 104.

- ^ Senelick 2000, p. 303.

- ^ Boyle 1989, pp. 11, 13–14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Davenport-Hines 2010.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 55, 61, 100.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 100.

- ^ a b McKenna 2014, p. 55.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b Baker & Burton 1994, p. 147.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2005, p. 30.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 102–105.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 65–67.

- ^ "Frederick William Park". Ancestry.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 65, 70.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 65.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 68–74, 113.

- ^ Clark 2020.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 73–74, 113.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 142.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Bartlett 1994, p. 289.

- ^ Upchurch 2000, p. 127.

- ^ Cohen 1996, p. 83.

- ^ a b Baker & Burton 1994, p. 148.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Senelick 1993, p. 87.

- ^ Upchurch 2000, pp. 127–128.

- ^ a b Cocks 2003, p. 105.

- ^ Senelick 1993, p. 89.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2005, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Upchurch 2000, p. 130.

- ^ Joseph 2019, 1297.

- ^ Kaplan 2002, p. 55.

- ^ Rowbotham 2015, p. 137.

- ^ a b Upchurch 2000, p. 131.

- ^ Brady 2009, p. 50.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 142.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 218.

- ^ Kaplan 2002, p. 46.

- ^ Joyce 2018, p. 886.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b "Police". The Times. 30 April 1870.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 9–11.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 32–35.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 35.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 40.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 89.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 42.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 50.

- ^ Pearsall 1969, p. 464.

- ^ Forth & Crozier 2005, p. 66.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 50–51.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 51.

- ^ a b c "The Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 30 May 1870.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 199.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 88.

- ^ a b c "The Extraordinary Charge Against the 'Gentlemen' in Women's Clothes". The Observer. 8 May 1870.

- ^ a b "The Charge of Personating Women". The Times. 7 May 1870.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 92–93.

- ^ "The Young Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 14 May 1870.

- ^ "The Young Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 16 May 1870.

- ^ "The Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 21 May 1870.

- ^ "The Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 23 May 1870.

- ^ "The Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 31 May 1870.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 26.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 116.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, pp. 42, 45–46.

- ^ "Release of Boulton and Park". The Times. 12 July 1870.

- ^ a b "Court of Queen's Bench, Westminster, May 9". The Times. 10 May 1871.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 43.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, pp. 35, 36.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 57.

- ^ White 2012, p. 45.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 300–301.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 250–251.

- ^ "Lord Arthur Clinton". The Guardian. 24 June 1870.

- ^ Kaplan 2002, p. 49; Cohen 1996, p. 79; Rowbotham 2015, p. 141.

- ^ a b McKenna 2014, p. 343.

- ^ Rowbotham 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Brady 2009, p. 237.

- ^ a b "Court of Queen's Bench, Westminster, May 15". The Times. 16 May 1871.

- ^ Report From the Select Committee on the Law and Practice relating to the Summoning, Attendance and Remuneration of Special and Common Juries, 8 July 1867, PP 1867 (425) IX. 597, p. 1. quoted in Cocks 2003, p. 121

- ^ a b Davenport-Hines 2004.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 87.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 89.

- ^ Rowbotham 2015, p. 142.

- ^ a b Pearsall 1969, p. 465.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 301.

- ^ McKenna 2014, pp. 315–316.

- ^ Cohen 1996, p. 118.

- ^ Reay 2009, p. 227.

- ^ Cocks 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 42.

- ^ Spencer 1995, p. 273.

- ^ Spencer 1995, p. 274.

- ^ Pearsall 1969, pp. 465–466.

- ^ a b c Cocks 2003, p. 106.

- ^ Senelick 2000, p. 304.

- ^ Baker & Burton 1994, p. 151.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 86.

- ^ "Judge's Chambers, 6 June". The Times. 7 June 1871.

- ^ "News". The Eastern Daily Press. 9 September 1871.

- ^ Senelick 2000, pp. 281, 296.

- ^ "News". The Fife Herald. 19 October 1871.

- ^ "News". The Bolton Chronicle. 21 October 1871.

- ^ Senelick 2000, p. 305.

- ^ Senelick 2000, p. 281.

- ^ McKenna 2014, p. 345.

- ^ Upchurch 2000, p. 128.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 24.

- ^ Upchurch 2000, p. 141.

- ^ "Leader". The Times. 16 May 1871.

- ^ Upchurch 2000, p. 137.

- ^ Kaplan 1999, p. 268.

- ^ Carriger 2013, p. 136.

- ^ a b Kaplan 1999, p. 282.

- ^ a b Carriger 2013, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Wileman 2015, p. 176.

- ^ "The Illustrated Police News: 'The worst newspaper in England'". British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Kaplan 2005, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Joyce 2018, p. 84.

- ^ Senelick 2000, p. 306.

- ^ Joyce 2018, p. 96.

- ^ Joyce 2018, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Joyce 2018, p. 85.

- ^ Boyd 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Stewart 1995, pp. 32, 141.

- ^ Stewart 1995, p. 141.

- ^ a b Cohen 1996, p. 75.

- ^ "Last Week's Latest News". Reynolds's Newspaper.

- ^ "drag". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Rosenman 2018, p. 190.

- ^ Hyde 1964, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b c d Cohen 1996, p. 124.

- ^ Matthewman 2010.

- ^ Vale 2015.

- ^ "Stella at Brighton Festival". The Brighton Festival.

- ^ "Stella". Holland Festival.

- ^ McLaren 1999, p. 125.

- ^ Arnold 2011, p. 263.

- ^ Kaplan 2002, p. 61.

Sources[edit]

Books[edit]

- Arnold, Catharine (2011). City of Sin: London and its Vices. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-8473-9372-2.

- Baker, Roger; Burton, Peter (1994). Drag: A History of Female Impersonation in the Performing Arts. Washington Square, NY: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1254-2.

- Bartlett, Neil (1994). "Evidence: 1870". In Goldberg, Jonathan (ed.). Reclaiming Sodom. New York: Routledge. pp. 288–299. ISBN 978-0-4159-0755-2.

- Boyd, Jason (2002). Aldrich, Robert; Wotherspoon, Garry (eds.). Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to World War II. London: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-15983-8.

- Boyle, Thomas (1989). Black Swine in the Sewers of Hampstead: Beneath the Surface of Victorian Sensationalism. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-81324-7.

- Brady, Sean (2009). Masculinity and Male Homosexuality in Britain, 1861–1913. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-23856-5.

- Cocks, H. G. (2003). Nameless Offences: Homosexual Desire in the 19th Century. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-86064-890-8.

- Cohen, William A (1996). "Privacy and Publicity in the Victorian Sex Scandal". Sex Scandal: The Private Parts of Victorian Fiction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 73–129. doi:10.1215/9780822398028-003. ISBN 978-0-8223-9802-8.

- Cook, Matt (2003). London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5218-2207-7.

- Crozier, Ivan (2005). "Striking at Sodom and Gomorrah: The Medicalization of Male Homosexuality and its Relation to the Law". In Stevenson, Kim; Rowbotham, Judith (eds.). Criminal Conversations: Victorian Crimes, Social Panic, and Moral Outrage. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. pp. 126–140. ISBN 978-0-8142-0973-8.

- Forth, Christopher E.; Crozier, Ivan (2005). Body Parts: Critical Explorations in Corporeality. Lanham, MA: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0933-5.

- Hyde, H. Montgomery (1964). A History of Pornography. London: Heinemann. OCLC 463500676.

- Joseph, Abigail (2019). Exquisite Materials: Episodes in the Queer History of Victorian Style. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-1-64453-170-9.

- Kaplan, Morris B. (2002). "'Men in Petticoats': Border Crossings in the Queer Case of Mr. Boulton and Mr. Park". In Gilbert, Pamela K. (ed.). Imagined Londons. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. pp. 45–68. ISBN 978-0-7914-8797-6.

- Kaplan, Morris B. (2005). Sodom on the Thames. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3678-9.

- McKenna, Neil (2014). Fanny and Stella: The Young Men Who Shocked Victorian England. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-5712-3191-1.

- McLaren, Angus (1999). Eder, Franz; Hekma, Gert; Hall, Lesley A. (eds.). Sexual Cultures in Europe: Themes in sexuality. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5321-4.

- Pearsall, Ronald (1969). The Worm in the Bud: The World of Victorian Sexuality. London: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-2971-7663-3.

- Rosenman, Ellen Bayuk (2018). Unauthorized Pleasures: Accounts of Victorian Erotic Experience. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-1870-0.

- Senelick, Laurence (1993). "Boys and Girls Together". In Ferris, Lesley (ed.). Crossing the Stage: Controversies on Cross-dressing. London: Routledge. pp. 80–95. ISBN 978-0-4150-6269-5.

- Senelick, Laurence (2000). The Changing Room: Sex, Drag and Theatre. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15986-9.

- Spencer, Colin (1995). Homosexuality: a History. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-1-8570-2143-1.

- Stewart, William (1995). Cassell's Queer Companion: A Dictionary of Lesbian and Gay Life and Culture. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-34301-0.

- Taylor, Alfred Swaine (1846). A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence. London: Churchill. OCLC 1048793679.

- Weeks, Jeffrey (1989). Sex, Politics and Society: The Regulation of Sexuality Since 1800. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-5820-2383-3.

- White, Chris (2012). Nineteenth-Century Writings on Homosexuality: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-74280-6.

- Wileman, Julie (2015). Past Crimes: Archaeological & Historical Evidence for Ancient Misdeeds. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-5979-1.

Journals and magazines[edit]

- Adut, Ari (July 2005). "A Theory of Scandal: Victorians, Homosexuality, and the Fall of Oscar Wilde". American Journal of Sociology. 111 (1): 213–248. doi:10.1086/428816. JSTOR 10.1086/428816. PMID 16240549. S2CID 40383920.

- Bristow, Joseph (January 2007). "Remapping the Sites of Modern Gay History: Legal Reform, Medico-Legal Thought, Homosexual Scandal, Erotic Geography". Journal of British Studies. 46 (1): 116–142. doi:10.1086/508401. JSTOR 508401. S2CID 145293550.

- Carriger, Michelle Liu (Winter 2013). ""The Unnatural History and Petticoat Mystery of Boulton and Park": A Victorian Sex Scandal and the Theatre Defense". TDR. 57 (4): 135–156. doi:10.1162/DRAM_a_00307. JSTOR 24584848. S2CID 57567739.

- Davenport-Hines, Richard (2004). "Lewis, Sir George Henry, first baronet (1833–1911)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34514. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Davenport-Hines, Richard (2010). "Boulton, (Thomas) Ernest (1847–1904)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39383. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Joyce, Simon (2018). "Two Women Walk into a Theatre Bathroom: The Fanny and Stella Trials as Trans Narrative". Victorian Review. 44 (1): 83–98. doi:10.1353/vcr.2018.0011.

- Kaplan, Morris B. (1999). "Who's Afraid of John Saul?: Urban Culture and the Politics of Desire in Late Victorian London". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 5 (3): 267–314. doi:10.1215/10642684-5-3-267. S2CID 140452093.

- Reay, Barry (March 2009). "Writing the Modern Histories of Homosexual England". The Historical Journal. 52 (1): 213–233. doi:10.1017/S0018246X08007371. JSTOR 40264164. S2CID 162357055.

- Rowbotham, Judith (27 March 2015). "A Deception on the Public: The Real Scandal of Boulton and Park". Liverpool Law Review. 36 (2): 123–145. doi:10.1007/s10991-015-9158-7. S2CID 144502598.

- Upchurch, Charles (April 2000). "Forgetting the Unthinkable: Cross Dressers and British Society in the Case of the Queen vs. Boulton and Others". Gender & History. 12 (1): 127–157. doi:10.1111/1468-0424.00174. JSTOR 0953–5233. S2CID 144295990.

News[edit]

- "The Charge of Personating Women". The Times. 7 May 1870. p. 11.

- "The Chronicle". The Bolton Chronicle. 21 October 1871. p. 5.

- "Court of Queen's Bench, Westminster, May 9". The Times. 10 May 1871. p. 11.

- "Court of Queen's Bench, Westminster, May 15". The Times. 16 May 1871. p. 11.

- "The Extraordinary Charge Against the 'Gentlemen' in Women's Clothes". The Observer. 8 May 1870. p. 8.

- "Judge's Chambers, 6 June". The Times. 7 June 1871. p. 10.

- "Last Week's Latest News". Reynolds's Newspaper. 29 May 1870. p. 5.

- "Leader". The Times. 16 May 1871. p. 9.

- "Lord Arthur Clinton". The Guardian. 24 June 1870. p. 2.

- "The Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 21 May 1870. p. 11.

- "The Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 23 May 1870. p. 13.

- "The Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 30 May 1870. p. 13.

- "The Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 31 May 1870. p. 11.

- "News". The Eastern Daily Press. 9 September 1871. p. 4.

- "News". The Fife Herald. 19 October 1871. p. 1.

- "Police". The Times. 30 April 1870. p. 11.

- "Release of Boulton and Park". The Times. 12 July 1870. p. 11.

- "The Young Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 14 May 1870. p. 10.

- "The Young Men in Women's Clothing". The Times. 16 May 1870. p. 13.

Websites[edit]

- Clark, Gregory (2020). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "drag". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 28 July 2020. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Frederick William Park in the Surrey, England, Church of England Baptisms, 1813–1917". Anglican Parish Registers. Woking, Surrey. Surrey County Council. 1847. Retrieved 6 July 2020.(subscription required)

- "The Illustrated Police News: 'The worst newspaper in England'". British Newspaper Archive. 19 April 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Matthewman, Scott (5 March 2010). "Lord Arthur's Bed review at Kings Head Theatre London". The Stage. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Stella". Holland Festival. 2016. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Stella at Brighton Festival". The Brighton Festival. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Vale, Paul (18 May 2015). "Fanny and Stella: The Shocking True Story". The Stage. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

External links[edit]

- 1870 in London

- 1871 in British law

- 1871 in London

- 19th century in LGBT history

- 19th-century scandals

- English LGBT entertainers

- Entertainer duos

- LGBT history in the United Kingdom

- LGBT-related controversies in the United Kingdom

- LGBT-related scandals

- Male-to-female cross-dressers

- Same-sex couples

- Sex scandals in the United Kingdom